Chad Ochocinco strode onto the field at Canton's Fawcett Stadium for this year's Hall of Fame Game wearing orange cleats. That was a no-no; the Bengals were slated to wear black shoes for the contest.

While it was one of the renegade wide receiver's tamer uniform shenanigans — more so than, say, the time he plastered a temporary "Ochocinco" nameplate on his uniform during his Chad Johnson days — it was a violation of the National Football League's dress code nonetheless. And it was Felix Wright's job to make it go away.

For 10 home dates a year, the 51-year-old former safety for the Browns serves as one of the NFL's 32 official uniform inspectors, emissaries employed at each stadium to maintain the sartorial sanity.

Wright has been the inspector at Browns games since 2001, but he also works the annual Hall of Fame Game, a preseason contest that marks the unofficial start of each season. He wandered over to talk to Ochocinco prior to kickoff last month and eventually managed to get him league approval for wearing the orange shoes just this one time. After all, the case to the league office went: He's only playing one series tonight.

Then Ochocinco emerged from the locker room just before kickoff with gold cleats on.

"They said I could wear these!" he insisted to Wright.

"No, you have you take those off. You were approved for the orange," Wright told him. "I was right there with you."

Wright's day begins two hours before kickoff, when he scrutinizes each team's pregame activities. "It's usually on the field before I can see it, but I have to police it," he says. "They know who I am. They know who all 32 [inspectors] are. Most guys will come over and ask 'Am I OK? Am I fine?'"

Those who aren't — untucked jerseys, socks exposed kneecaps, unauthorized shoes, etc. — are logged on a report by Wright. One copy of it goes to the NFL; another goes to a designated member on each team — usually an equipment or strength coach, who then goes over the list in the locker room before kickoff, reminding each player what Wright griped about.

If they emerge from the tunnel with all infractions corrected, Wright simply checks off their name. If not, the league seeks input from the inspector as to whether a fine is in order; most times, if the problem is remedied before the first whistle, the player escapes monetary punishment — the very threat of which is usually enough to persuade them to adjust the offending garments.

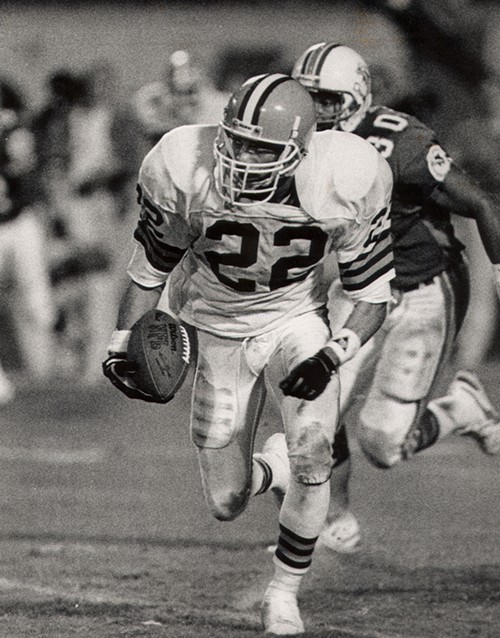

- Wright back in his playing days.

Wright then logs another report throughout the game, for which the stakes are considerably higher. During the preseason — when fans mostly aren't following the action on the field anyway — fines start at $5,000. The price goes up for the regular season, with exact dollar amounts depending on the severity and frequency.

"Most guys don't like getting fined," Wright says. "All it usually takes is one hit. What I tell guys is, don't look at me as the bad guy. I'm keeping money in your pocket. Ultimately I'm the guy that's going to help you not get fined."

Take Josh Cribbs, who for a couple of games last year took to wearing socks on his arm as though he were auditioning for an '80s rock band. Wright popped him with a write-up, the NFL levied a fine, and the offending hosiery disappeared.

Of course, some jocks just don't care. Feisty former Browns Braylon Edwards and Kellen Winslow share that distinction.

"Braylon and Kellen would come out and just say, 'I'll take the hit,'" Wright says. "Braylon wouldn't wear any socks. He'd have footies on, he would wear his shirt under his pads. I used to tell him, if you're going to give money away, give it to your mom. Don't give it back. Why would you want to give up $10,000 just because you don't have socks on?

"The guys up top are watching too," Wright adds. "It's not just me."

He isn't kidding. Everything — from jerseys being properly tucked in to height of socks to brand of shoes to the color of the chinstrap — is addressed under the league's rules and regulations. While Wright says he is not reprimanded or judged based on his performance, if he misses something, the NFL is bound to catch it. Whether an oversight leads to a later fine or an immediate phone call depends on the situation. If it's Monday Night Football, for instance, expect a call.

"It's easy to make fun of them — call them the fashion police or whatever, but the NFL has maintained a better look in terms of consistency in uniform than, say, Major League Baseball," says Paul Lukas, who covers the uniform beat (yes, there is such a thing) for espn.com and his blog, uniwatchblog.com.

"You can call it whatever you want. It comes from the same place as the control-freak aspects of the NFL, the corporate controls, but it's led to a better-looking product compared to some other leagues. You have to believe if the players had their way, they would wear anything."

But it's about more than just what the players are wearing; it's about brand management.

The NFL is uncannily adept at capitalizing on its popularity through sponsorship deals, contracts which allow companies like Reebok and Gatorade and Motorola to become the official and sole providers of services and have their logo splashed around the stadium. It's a lucrative business, one the NFL goes to great lengths to protect. Reebok's deal, for instance, paid $250 million over ten years.

That kind of coin buys you the efforts of henchmen to keep Nike logos off the field.

It was one of the first lessons Wright learned from his predecessors in the job, former Browns Gary Jeter and Eddie Johnson. "'You're here to protect the sponsorships of the NFL,' they'd say to me."

That means no Adidas, no Nike, no Powerade, no Lucent. And no Coke or Pepsi, products seemingly incongruous with high-level athletic pursuits, but which Wright often finds on the field anyway.

"It's wild that the stuff gets down there, but it gets down there," he says.

Wright's domain extends into the locker room too, where he sticks around two hours following the final whistle to monitor coaches and players on both teams appearing on camera during interviews. Same rules: No logos of competing companies. If it's not a sponsor, you're not wearing it, you're not holding it.

But if the players seem woefully uneducated when it comes to the rules, it might be because they don't receive much internal guidance. The coaches, Wright says, are often worse than the players when it comes to blowing off league policy.

As evidence, he recounts a recent episode of the HBO reality series Hard Knocks, which this year is chronicling the New York Jets. "I want to talk to you about the uniform rules," head coach Rex Ryan informs his team. "Wear your uniform."

"Then he broke the meeting," Wright says with a laugh. "He doesn't care."

He might not care now, but some of the Jets may, including Braylon Edwards, when New York visits Cleveland to play the Browns on November 14.

Wright will be there waiting, undoubtedly looking at Edwards' socks.

Follow me on Twitter: @vincethepolack