Shauna Smith sat in the courtroom each day, nausea knotting her stomach, as lawyers tussled over the details of how a Cleveland police officer killed her son.

The trial stretched over a week last September on the 19th floor of the Federal Building downtown. Witnesses climbed into the stand before Judge Solomon Oliver and the eleven jurors, each speaker reeling off first-hand accounts or expert testimony.

Smith, a baby-faced South Euclid woman topped with a swirl of reddish hair, absorbed everything — blood-flecked crime scene photos; grisly autopsy reports; the words of the very officer who pulled the trigger. The sum total of the trial essentially ripped off the emotional bandages she'd worn for the past two years after the death of her son.

"It was like reliving everything," Smith recalls today. "It was an awful experience." In March 2012, Smith's son Kenny, a promising rapper then riding an express elevator to the top of the local hip-hop talent heap, was in a downtown bar when a fight spilled out into the parking lot. Gunshots ripped the night. The 20-year-old jumped into the car of a friend from the neighborhood. An off-duty Cleveland police officer named Roger Jones, thinking the car contained the shooter, ran to the vehicle with his gun drawn. Moments later, another gunshot, this time from the off-duty cop's gun. Jones, and police officials, quickly said in the aftermath that Kenny had been shot while reaching for a gun in the car.

Officer Jones "correctly and heroically took action to protect the safety of the citizens of Cleveland," Cuyahoga County prosecutor Tim McGinty said in a letter to Cleveland Police Chief Calvin D. Williams after McGinty's office ruled the shooting was justified.

But now, inside a federal courtroom three years later, that official account was toppling over.

Smith's attorneys Terry Gilbert and Jacqueline Greene argued Officer Jones had violated Kenny Smith's civil rights with an unjustified use of deadly force. They dismantled the city and Jones' story with the help of an eyewitness who had watched Smith die outside the car, with his hands up. Physical evidence — there was no blood in the car — backed up the scenario. The city's version of the story — that Smith was shot in the head, then walked a few steps onto the pavement where he expired — came off as implausible.

So confidence was high as the jury packed up for deliberations on the morning of Sept. 8. Smith and her family members barely had time to get settled in the courthouse cafeteria for the wait when they were told the jury was back. It was before noon.

Shauna Smith was sunk in an expectant daze as the jury handed over their decision. Slowly the words began tumbling from Judge Oliver, a storm of legalese filling Smith's confused ears. Only when the judge began reading dollar amounts did she realize they'd won: $4.5 million for the wrongful death, $1 million for Kenny's survivors. Her face wet with tears, Smith wrapped her attorneys in hugs, ready to finally push on into a different part of her life. Her son's death had occasioned the second-largest civil judgment against a Cleveland officer in recent history.

"It was joyful," Smith recalls today. "I thought now at least I could move forward with my life, try to live normally."

But thanks to some crafty moves from the city's law department, Smith's moment of justice might never come.

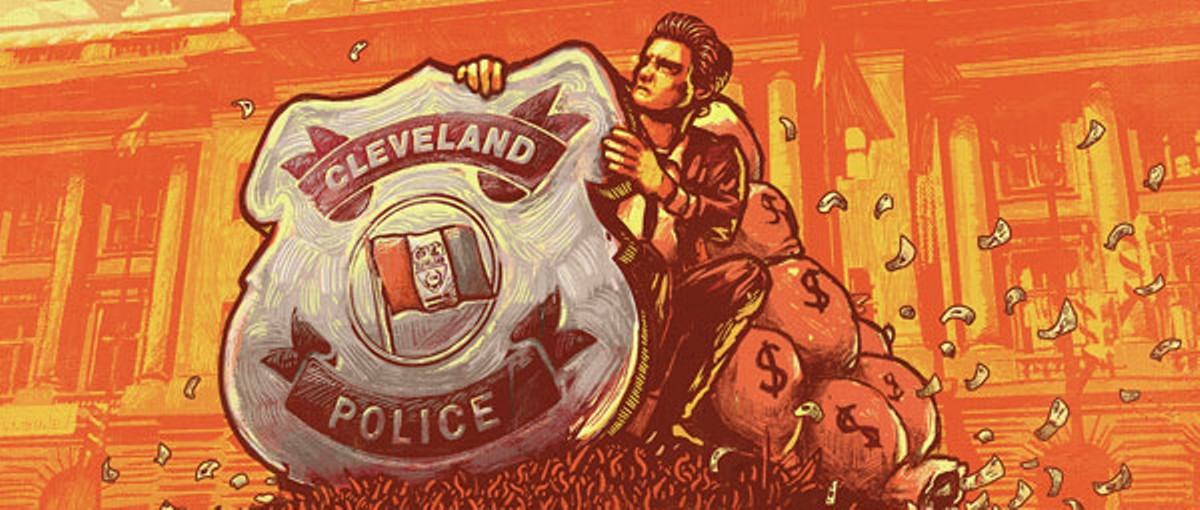

Across the country, piggy bank-busting civil judgments have become the best way to keep police and municipalities honest in cases of officer misconduct. From 2004 to 2014, for instance, Cleveland shelled out $10.5 million in settlement money to victims of badly behaving cops. Under state law and the terms of the union contract, chronically cash-strapped Cleveland indemnifies officers in the cases where they've been personally found liable, meaning ultimately, taxpayers foot the bill for an officer's misconduct.

But now, in the two largest civil judgments currently sitting on the books — one being Kenny Smith's death; the other a sloppy and malicious murder investigation that railroaded an innocent man — the city has pulled a move that one veteran civil rights lawyer calls "wrong, immoral, disingenuous and unethical."

In both cases, the Cleveland law department used city funds to pay for cops saddled with judgments to move into personal bankruptcy. It's a calculated effort, according to the attorneys fighting the move, for the city to skip out on their responsibilities to pay the judgments.

The screwjob burns all the more after the parade of black eyes the city has suffered due to cops and criminal justice. Just as mayor Frank Jackson, clutching the Department of Justice's 2014 consent decree, promised citywide soul-searching on police reform, Cleveland's law department is messing with civil matters that have already been decided by a jury.

And the implications aren't only local.

"This provides a road map for any municipality that wants to evade their obligations," says Ruth Brown, a Chicago attorney currently locked in legal judo with Cleveland over the issue. "We fully expect that if Cleveland is allowed to get away with this, they will try this again."

***

The clerks who were catching incoming filings at the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in the Northern District of Ohio in July 2013 wouldn't have had much reason to run more than a bored eye over the 52-page filing stamped with Denise Kovach's name.

The retired Cleveland police detective listed the usual ho-hum stack of assets: an $82,500 Brecksville home; $66,000 in a public employee retirement plan; $63 in cash; a $250 9mm Smith and Wesson; two toy poodles checking in at $500.

But a closer look would have spotted a surprise in the debt column: $13.2 million, all owed to a man named David Ayers. "Federal Section 1983 Claim," the listing notes, "rendered March 2013."

In December 1999, David Ayers was a Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority security guard when a 76-year-old woman was found beaten to death in the authority-owned high-rise Ayers called home as part of his job. CMHA police and the Cleveland detectives assigned to the case, Denise Kovach and Michael Cipo, put Ayers in the crosshairs of their investigation, despite zero concrete evidence tethering him to the death.

Instead, the detectives made false statements in search warrant affidavits; testified Ayers made a partial confession (even though neither noted such a statement in their case notes — case notes, incidentally, which take the time to point out when an interviewee appeared "gay like"); forced a friend of Ayers to sign a false affidavit (the friend later said he was coerced into signing); declined to follow-up on (and later didn't tell defense attorneys about) a recent fight the victim had had with a family member who was stealing her money; and dispatched a jailhouse snitch, armed with details of the case, to chat up Ayers in jail. At trial, that snitch, Donald Hutchinson, told a jury the former CMHA officer confessed to the crime.

All this — what a later 2013 appellate court judge would call sufficient "evidence that Detectives Cipo and Kovach conspired to violate [Ayers'] civil rights" — secured Ayers' conviction in March 2000. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

So began a 11-year legal brawl, with Ayers and his attorneys from the Ohio Innocence Project mounting a series of state and federal appeals to right the wrongful conviction. Finally, in 2011, DNA evidence secured from pubic hairs found on the body of the victim was tested. It failed to match Ayers. He was exonerated, and quickly launched a federal lawsuit, known as a Federal Section 1983 claim, against the city, CHMA, and the detectives who engineered his railroading. Lawyers for the city of Cleveland law department represented the officers when the case found its way to trial in early 2013.

That March, jurors found that, yes, Kovach and Cipo had violated Ayers' rights with their investigation and arrest. The exoneree was awarded a $13.2 million judgment against the two detectives, the largest such judgment at the time.

But Ayers' happy financial ending wasn't in the offing. As records now indicate, a month after the verdict, Cleveland Law Director Barbara Langhenry signed a contract with a Broadview Heights attorney named David Leneghan to represent Kovach and Cipo. The detectives "have requested legal representation to assist them with personal, individual bankruptcy proceedings," the contract stated.

Cipo never got a chance: He died in July 2013. But later that month, Kovach dropped her 52-page Chapter 7 filing on the district court, including the tallies of assets (toy poodles, Smith & Wesson) and debts, including $6,000 in credit, and nearly $13 million for the Federal Section 1983 claim.

By November, with a routine snap of a bankruptcy judge's pen, the millions Ayers had earned from his decade in hell were swept away, and with it, apparently to the city's thinking at least, Cleveland's obligation to foot the bill for the bad cops and the justice awarded by the jury.

***

"We became notified the officer was filing for bankruptcy, and basically realized Cleveland had engaged in a wrongful scheme to evade the judgment," explains Ruth Brown, one of Ayers' attorneys at the Chicago firm Loevy & Loevy.

In a typical case where a city employee has been slapped with a civil lawsuit, the Ohio Revised Code dictates the municipality has the "duty to defend" the employee as long as they were "acting both in good faith and not manifestly outside the scope of employment or official responsibilities." So too with indemnification: If the employee meets those two requirements and is found liable for a civil judgment, the law says the city indemnifies — or picks up the tab.

This tracks nationally. "Police officers are virtually always indemnified," wrote UCLA law professor Joanna C. Schwartz in a 2014 study that crunched data on settlements from the country's largest police departments, including the Cleveland PD. Overall, Schwartz found that cities indemnify officers in 99.98 percent of the cases she studied.

"Between 2006 and 2011, in forty-four of the country's largest jurisdictions, officers financially contributed to settlements and judgments in just .41 percent of the approximately 9,225 civil rights damages actions resolved in plaintiff's favor," she wrote. "[A]nd their contributions amounted to just .02 percent of the over $730 million spent by cities, counties and states in these cases."

Interestingly, Schwartz found that Cleveland was one of the few municipalities that hadn't fully indemnified officers in two cases out of the 35 local civil rights actions resolved in favor of the plaintiff that she examined.

In one case, Cleveland officers beat up a handcuffed driver after an auto accident during an unrelated 2007 car chase. One of the cops was criminally charged from the incident and later fronted $25,000 of the total $45,000 paid to the victim. The other case stemmed from a 2009 lawsuit ignited when an off-duty Cleveland police officer working security at a housing complex shot and killed a resident. The officer eventually paid $12,000 of the total $47,000 payout.

However these cases, where the incident was outside of the scope of the officer's employment or led to criminal charges — i.e., was done in bad faith — have little in common with the Ayers case.

But rather than indemnify per state law in that case, the city paid for the officers to enter bankruptcy — paying not only for their legal representation, but for their filing fee. Not to think about going into bankruptcy, Ayers' attorney Brown points out, but to dive right in.

"I think it's really clear when you look at the contract that the purpose was not to provide the officers with neutral, unbiased legal advice," she explains. "It was to ensure they filed for bankruptcy right away."

For one, the contract didn't pay the attorney by the hour, but instead forked over a $1,000 lump sum for each bankruptcy. "This is pretty unusual," Brown argues. The contract also does not compensate the bankruptcy attorney for any legal research; in fact, the attorney must get permission from the city's law department to undertake any research, discouraging the officers from finding an alternative to bankruptcy.

So why would the city want its officers to go into bankruptcy? To flush away the judgment without indemnifying the officers, Ayers' lawyers claim. As Brown points out, when Kovach's filing actually hit the court, nowhere in the document did it mention Kovach had a right to indemnification for the Ayers debt.