Earlier this month, a loose coalition of black activist organizations pulled petitions for the recall of Frank Jackson, the longest-serving mayor in Cleveland's history. The coalition argued that local leaders must be held accountable.

In a video explaining the effort, organizer Jeff Mixon said that Jackson, Cuyahoga County executive Armond Budish and congresswoman Marcia Fudge, among others, were leaders who had sold out, and were now serving the corporate community at residents' expense.

An affidavit explaining the reasons for the recall attempt described Jackson as an "ineffective" leader.

Alas, Jackson's effectiveness is difficult to assess, given that on the campaign trail in 2017, he laid out no goals or plans for his fourth term in office, beyond "continuing what [he] had been doing." Tactically, or at any rate linguistically, this was an ingenious ploy. Critics cannot call him ineffective if there's nothing to measure his effectiveness against.

In limited campaign appearances, Jackson's 2017 strategy was merely to wave away his opponents, only two of whom represented legitimate challenges to his incumbency. His message, if he had one, was that during his fourth term — the current term — Cleveland would witness the completion of projects he'd spent his first three terms carefully creating the conditions for. The only metric for success he applied to himself was one that he has repeated at virtually every State of the City address since 2013. He should be measured, he said, by how the city treats "the least of us."

If he took that slogan seriously, he would resign in disgrace.

As 2019 marches onward, certain of Jackson's oft-criticized tendencies have grown much worse. These include hostility toward the press, blind loyalty toward his friends, certitude in his motives, stubbornness in all things, and an abiding preference for privacy, which in public life means a preference for concealment.

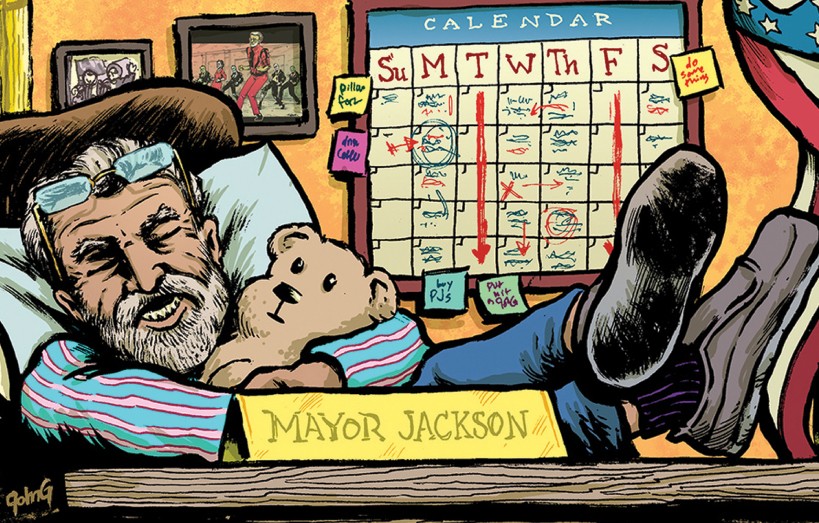

What the recall coalition has correctly identified is that there's not much to conceal. The perception that Jackson was asleep at the wheel through 2018 turns out to be mostly true. (Sometimes literally: According to the media rumor mill, when a reporter arrived at City Hall to interview Jackson in the wake of the Aisha Fraser murder in November, the mayor reportedly had to be awoken from a nap at his desk.)

Scene dubbed the Jackson administration the "zombie incumbency" in 2017, but that characterization has become much too generous. The mayor only arises from the dead, evidently, to campaign. His essential function these days is to potter around to birthday parties, funerals and ribbon cuttings in between routine briefings with his chief advisors and big wigs. His eyes, if you catch them at a ground breaking or retirement celebration, are glassy and mournful, less tranquil than tranquilized, aimed at nothing and nobody at all.

Incidentally, are you Cleveland.com editor Chris Quinn? If not, that means you're not one of very few people who still meets with Jackson monthly and who may have some insight into how he thinks and behaves. The rest of us are in the dark. A notoriously hermetic City Hall became even more bottled up in 2018. There was much hand-wringing over the Amazon HQ2 bid's secrecy — all those "proprietary" "trade secret" excuses that were used to deflect media requests — but that incident was typical.

For a more recent example, take the minor security breach at Hopkins Airport in November, in which Jackson's chief operating officer Darnell Brown bypassed security after retrieving a forgotten laptop from his car. City spokesman Dan Williams told Cleveland.com that the city's report on the incident would remain confidential because it contained information on airport security. That was a lie. In a follow-up story, TSA's Ohio security director said that nothing in the report would be deemed confidential until TSA said so. And the city hadn't even submitted the report to TSA yet, so Williams was just making things up.

In a story last week, Cleveland.com's city hall reporter Bob Higgs noted that city council, which has the authority to hold public oversight hearings and budge the administration from its secrecy, rarely does so. Not for the Hopkins indiscretion; not for the mysterious collapse of an agreement to purchase 1801 Superior Avenue, home of Cleveland.com, for the city's new police headquarters; nor for any other important city issue.

This is all par for the course. Years ago, Jackson candidly (and amusedly) admitted to a roomful of reporters that city spokespeople often declare that information is "proprietary" when the mayor hasn't had a chance to review it.

Serial host Sarah Koenig told Scene, shortly before the podcast's most recent season premiered, that she and co-host Emmanuel Dzotsi failed to get a single on-record interview with City of Cleveland officials during their many months of reporting.

"We tried and tried," she said. "It was very difficult because they just did not want to talk to us ... I really felt for [local reporters]. It would make me insane. Whenever I see information in Cleveland now, I realize how hard reporters had to work to get it. The city is not forthcoming. And not to get too high-falutin', but it's a problem for democracy."

The administration takes cues from Jackson himself, who has retreated into recluse mode. Comparing his media availability from 2017, when he was on the campaign trail, to 2018, is astonishing. In 2017, he appeared on Sound of Ideas, WCPN's morning news program, three times. He held press conferences explaining or launching various city initiatives at least once per week through July and September. He set aside time for one-on-one interviews with local and national journalists. He sat for regular Facebook live videos, so that constituents (and the press) could watch him talk informally about issues of importance to him. It was on Facebook live that Jackson signed the Q Deal legislation, for example, calling it "one of the best deals the City of Cleveland has ever made."

This is nothing compared to years past, of course, when mayors or their spokespeople would traditionally hold daily press briefings to provide updates on ongoing projects and to answer questions on a wide range of topics.

But still.

In 2018, Jackson disappeared. Other than his monthly meetings with Chris Quinn (about which Scene reported in March 2017), he rarely interacted with the media at all. After a press conference on July 26, noted in his daily calendar alongside a meeting "with CEOs," there isn't a single record of a media appearance until Oct. 11, when he made himself available for interviews the day after his State of the City address.

In November, Jackson spoke with reporters in the tense aftermath of Aisha Fraser's murder, defending the city's hiring of Lance Mason. In December, he swung at softballs from WKYC's Leon Bibb in what might have been — or might as well have been — a coordinated promotion of the Mayor's Neighborhood Transformation Initiative in Glenville. And that's it.

We needn't belabor the fact that this posture from City Hall, and the concomitant effects on the availability of information, is compounded by the diminished number of working journalists. Given the lack, or misallocation, of resources, it's unrealistic for an enterprising reporter to trail Jackson for weeks on end in an attempt to figure out what he's up to. And given that the media relations team seldom does any relating with us, our best option is to consult the documentary record, which in this case means consulting the mayor's daily calendar. The city is still compelled, under public records laws, to furnish those documents when they are requested. (We happily report that the documents were provided in a timely manner through GovQ&A, the city's public records portal).

Scene examined and tabulated every non-redacted item from Mayor Jackson's 2017 and 2018 calendars on the following working theory: If we can determine the priorities of a city by how it spends its money, we should be able to determine the priorities of a mayor by how he spends his time.

Here's what we found:

'ABSOLUTELY NO APPOINTMENTS'

While the total number of the mayor's scheduled appointments declined sharply through 2018's second half, so too did the blocks of time that he made himself available.

Beginning in earnest in March, the mayor tends to reserve Tuesdays entirely for himself. He does the same Thursday mornings and Friday afternoons. It's unknown what he does during these substantial chunks of time. But "ABSOLUTELY NO APPOINTMENTS!!!" appears like clockwork from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. every Tuesday; 8 to 11 a.m. every Thursday; and, generally, noon to 6 p.m. every Friday.

(For the record, Scene submitted by email a series of specific questions related to the mayor's activity for this story, including one that sought clarification on the "ABSOLUTELY NO APPOINTMENTS" designation. Those questions went predictably unanswered.)

The bulk of the mayor's most important regular meetings — a weekly briefing with his top chiefs; a weekly legislative review with chief of government and international affairs Valarie McCall; a weekly briefing on CMSD activities with Eric Gordon and chief of education Monyka Price and others; a weekly meeting of the Board of Control; a bi-weekly meeting of his full cabinet; monthly catch-ups with council president Kevin Kelley, Cuyahoga executive Armond Budish, consent decree monitor Matthew Barge and local consent decree coordinator Gregory White — occur on Mondays and Wednesdays. The two exceptions are a weekly public safety briefing with police chief Calvin Williams and safety director Michael McGrath, which happens Thursday afternoons, and a briefing with chief of staff Sharon Dumas, COO Darnell Brown, and chief of regional development Ed Rybka on Friday mornings.

BUSINESS OF THE CITY

There were very few "NOT PUBLIC RECORD" redactions in the latter half of 2018. When information was redacted (blacked out), the city justified it on grounds that the concealed information did not "document the business of the city." (For reporting on a prior story, Scene learned by accident that Jackson's haircuts had been thus redacted.)

In 2017, by contrast, there were well over 200 such redactions, most of them concentrated in the summer and fall. The likely explanation is that these redactions concealed campaign activity, most of which was conducted during business hours.

Due to this activity, the mayor appears to have performed, at most, 14 hours of official work on city business the week before the 2017 primary election. That work was mostly ceremonial, including a photo op with a Browns Backers chapter and attending the Cleveland Browns game (if he stayed for two hours, as his calendar suggests).

Much of October 2017 is similarly overrun with redacted items. It's difficult to determine the exact time slots, but the week before the general election, Jackson appears to have performed, at most, 13 hours of official work on city business. Again, much of this stuff was indistinguishable from campaign activity: attending the Big City Boo celebration at Michael Zone Rec Center, standing for a couple of photo-ops; attending the 1st District Community Relations Award ceremony, and giving brief remarks at a weekend pancake breakfast in Ward 12.

ATTORNEY-CLIENT PRIVILEGE

The redaction that persists is a single item every Friday morning, concealed on the grounds of "Attorney-Client Privilege." We have no explanation. Maybe it's a meeting that was auto-filled some time ago?

WHAT ABOUT LEISURE TIME?

In two years, it doesn't look like Jackson has taken any official vacation time, ABSOLUTELY NO APPOINTMENTS notwithstanding. However, for three weeks in May (May 7 through May 27), he canceled virtually every meeting he had scheduled. Some of the regular meetings were not marked as canceled, but may have been. He conducted a series of swearings-in on Monday, May 14, but had so few items on his calendar during that stretch that it might as well have been vacation or a stretch during which he attended to personal matters.

AN AUDIENCE WITH FRANK

Jackson met with a broad assortment of leaders and community figures in 2018. Though his inner circle sees him most often, he also touches base with the heads of the local hospitals and universities, and regularly takes introductory meetings with business and community leaders. He occasionally meets individually with council members as well. While he attended the most events with or for councilman Blaine Griffin in 2018, he met most often one-on-one with new councilman Basheer Jones.

Weekly Meetings: Chiefs; Valarie McCall (Chief of Government and International Affairs); Eric Gordon (CEO, CMSD); Monyka Price (Chief of Education); Board of Control; Calvin Williams (Chief of Police); Michael McGrath (Director of Public Safety); Sharon Dumas (Chief of Staff); Darnell Brown (COO); Ed Rybka (Chief of Regional Development).

Bi-Weekly Meetings: Cabinet.

Monthly Meetings: Kevin Kelley (Cleveland City Council President); Armond Budish (Cuyahoga County Executive); Matthew Barge (consent decree monitor); Judge Gregory White (DOJ); Chris Quinn (editor, Cleveland.com).

Quarterly Meetings: Akram Boutros (CEO, MetroHealth); Tommy Mihaljevic (CEO, Cleveland Clinic); Tom Zenty (CEO, UH); Steve Standley (Chief Administrative Officer, UH); Will Friedman (CEO, Port of Cleveland); Darrell McNair (board chair, Port of Cleveland).

Multiple Meetings (bi-monthly or no set schedule): Michael Cox (Director of Public Works); Matt Gray (Chief of Sustainability); Duane Deskins (Chief of Youth Violence Prevention, pre-resignation); Tracy Martin-Thompson (Chief of Youth Violence Prevention); David Ebersole (Director of Economic Development); Natoya Walker Minor (Chief of Public Affairs); Carole Hoover (consultant, power broker); Fred Ward (community organizer); Basheer Jones (councilman, Ward 7); Say Yes to Education Planning; Transformation Alliance.

1-2 Meetings: David Abbott, (Gund Foundation); Roland Anglin, (CSU Levin School); Jim Barna, (Drive Ohio); Michael Bowen, (Campaign Manager); Brendan Buescher, (McKinsey); Gene Chasin (Say Yes to Education); Joe Cimperman, (Global Cleveland); Phyllis Cleveland, (Councilwoman, Ward 5); Kathleen Clyde, (State Rep., Secretary of State candidate); Chris Connor, (Sherwin-Williams); Kevin Conwell, (Councilman, Ward 9); DeMario Cooper, (Ohio Organizing Collaborative); David Coopperrider, (CWRU); Richard Cordray, (Gov. candidate); Toby Cosgrove, (Cleveland Clinic); Cary Dabney, (Cleveland Catholic Diocese); Amber Donovan, (Open Table); Umberto Fedeli (Fedeli Group, donor); Marty Flask, (Executive Assistant); Mike Gammella, (Mayor of Brookpark); Fred Geis, (Geis Cos.); Christopher Gergen, (Forward Cities); David Gilbert, (Destination Cleveland); Marcie Goodman, (CIFF); Blaine Griffin, (Councilman, Ward 6); Anthony Hairston, (Councilman, Ward 10); Brian Hall, (Greater Cleveland Partnership); Dr. Gregory Hall, (physician); Maia Hanson, (McKinsey); Ken Hardy, (Bonnie Speed Logistics); Greg Harris, (Rock Hall); Justin Herdman, (US Attorney); Kerrie Howard, (Judicial Candidate); Dr. Edgar Jackson, (NEOMED); Michael Johnson, (John Carroll University); Joe Jones, (Councilman, Ward 1), India Pierce Lee, (Cleveland Foundation); Dennis Lehman, (Cleveland Indians); Kerry McCormack, (Councilman, Ward 3); Stephen McHale, (Explorys, Unify Project); Vincent Montague, (Black Shield); Beth Mooney (Keybank); Bernie Moreno, (Blockland); Fred Nance, (Squire Patton Boggs), Mike O’Malley, (County Prosecutor); Dominic Ozanne, (Ozanne Construction); Plain Dealer Editorial Board; David Quolke, (Cleveland Teachers Union); Al Ratner, (Forest City, Power Broker); Chris Ronayne, (University Circle Inc.); Harlan Sands, (CSU); Jasmin Santana, (Councilwoman, Ward 14); Tariq Seifullah; Ken Silliman, (Former Chief of Staff); Barbara Snyder, (CWRU); Ron Soeder, (Boys & Girls Club); Matt Spronz, (Director of Capital Projects); Jerry Sue Thornton, (Formerly Tri-C, Power Broker); Jimmy Traynor, (West Side Market); Stephanie Turner; Eric Tyler; Ben Vinson (CWRU); David Weiss, (Shaker Heights Mayor); Ernest Wilkerson, (Accountant); Sandra Williams, (State Senator); Barry Withers, (Former Director of Public Utilities); Dave Wondolowski, (Construction Unions); Brian Zimmerman, (Metroparks); Matt Zone, (Councilman, Ward 15).

VALARIE IS EVERYWHERE

Many of Jackson's top chiefs are women. Among them: chief of staff Sharon Dumas, law director Barbara Langhenry, public affairs chief Natoya Walker Minor, education chief Monyka Price, community development director Tania Menesse, building and housing director Ayonna Blue Donald; and public health director Merle Gordon.

But Jackson's closest advisor is Valarie McCall, dubbed the "mayorette" long ago by a former city hall reporter. She is everywhere in Jackson's calendar. In addition to her weekly "legislative review" on Monday mornings, she frequently sits in on important meetings with the mayor and serves as coordinator and point person for most of his evening activities.

SHOWING UP

In 2017 and 2018, Jackson attended more than 50 funerals and/or wakes for prominent city figures or close friends and family of city hall staffers and community leaders.

One can easily mock the vice-presidential character of attending funerals, but Jackson seems to recognize the value of his presence at these events. The fact that he continues to attend them, even after election season, will receive no mockery from Scene.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Through the latter half of 2018, the region was abuzz with conversations about supposedly bold, supposedly new economic development strategies. Jon Pinney gave that City Club speech in June. Auto mogul Bernie Moreno roused an army of civic leaders to participate in his crusade to make Cleveland a blockchain hub. Low-beam luminaries from the economic development sector were penning op-eds in the business press on what felt like an hourly basis. Forums and panels and summits were convened for the planning of future forums and panels and summits.

Whether or not these conversations will yield positive results for the region remains unknown. But Mayor Jackson was not a part of them.

Neither Jackson nor a representative from his administration attended a December summit hosted by Cleveland.com. Columnist Mark Naymik said that Jackson's absence "had to be called out" because attendance should have been "a no brainer." The subject, economic inclusion, was "near and dear to [Jackson]" and "after 13 years in control of City Hall, his administration could benefit from some new ideas, visions and inspiration." Scene had heard that Jackson specifically instructed the invited members of his administration (Freddy Collier and Tania Menesse) not to attend.

Jackson did meet with Bernie Moreno in June and let Bernie speak to his cabinet about blockchain. He also gave brief remarks at the Blockland conference in December, and spoke about the potential of technology in the classroom and in the hospitals at his state of the city address. But Jackson's economic development priorities — the Neighborhood Transformation Initiative, continual improvements at CMSD — have recently occurred adjacent to, not in concert with, the flashy moonshots of the private sector (public funding for sports stadiums excepted.)

THE PARALYSIS OF ROUTINE

Jackson is a creature of habit. His weekly schedule is by now routinized, almost mechanized, such that he's able to manage and communicate with his top chiefs regularly.

But routines of this sort can have a paralyzing effect. Reading through recent months of the mayor's activity, one recalls that very little of substance was accomplished in 2018. Councilman Mike Polensek, in an existential paroxysm two weeks ago, asked Scene what he was even doing here [on council]. What had he been elected for? What was the point? Polensek was quoted in Bob Higgs' oversight story last week, arguing (contra Kevin Kelley) that council should be holding the mayor accountable much more actively. He has made identical comments to Scene.

Brent Larkin noted in a Plain Dealer column Sunday that "no place on earth does a better job talking about its problems than [Cleveland]." And while there was perhaps an unusual amount of chatter about solutions and "transformation" in 2018, there wasn't much action. Most of City council's ordinances, for example, merely authorized annual disbursement of funds or contract renewals. Jackson's big policy push was getting trauma coaches at city rec centers. That's laudable, no doubt, but by no means a total year's worth of mayoral accomplishments.

Jackson's calendar describes the duties of a queen, not a prime minister. He devotes regular time to the dignitarial aspects of his position: the photo-ops, the visits with CMSD students, the award ceremonies and cupcake sendoffs. But he's not using his bully pulpit to publicly take charge of critical conversations. Nor is he pushing for progressive urban policy as other mayors across the country are.

In California, Washington, Colorado and New York, mayors are working with state bodies to wipe low-level marijuana convictions. In Minneapolis, radical rezoning pushed by mayor Jacob Frey will drastically increase the availability of affordable housing. In Los Angeles, mayor Eric Garcetti has increased taxes to fund, not sports facilities, but mass transit. Closer to home, on a more symbolic level, Akron mayor Dan Horrigan rode the bus in December with other Summit County public officials to promote public transportation. Toledo's mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz has said that the city's future "hinges on" public transit and vowed to take the bus to work once a week for the duration of his term. Dayton mayor Nan Whaley, who proposed a tax on drug companies (a nickel per pill) to combat opioid overdoses, has become a national voice on the epidemic.

What is Frank Jackson's sweeping reform?

For that matter, what is his legacy? The length of his tenure? "It is what it is"? Whatever it is, the paralysis of routine isn't the only thing keeping him from pursuing a legacy. His convictions may also, counterintuitively, play a role. Our sources at city hall swear up and down that Jackson sincerely cares for the poor and downtrodden. His inaction on lead, for example, reportedly stems from his fear that if landlords are forced to get lead-safe certificates, poor people will bear the brunt of that policy. They'll be kicked out of their homes with no place to turn. On criminal justice, when the DOJ published its scathing report on police misconduct in Cleveland in 2014, Jackson's objection, which he uttered repeatedly, was that "it didn't go far enough."

But instead of formulating policy to guard against the outcomes he fears, or to push for solutions that address root causes — or even to articulate these positions in a consistent way to anyone other than Chris Quinn — Jackson's tendency is to do nothing, to not rock the boat, to not make matters worse.

And that's great for folks who are already doing well: donors and suburban dwellers preoccupied with things like the downtown renaissance narrative. Jackson's overwhelming support from the business community, we remember, is predicated on his "stability."

"[Jackson] has capably and fearlessly taken on many crises head on, providing the sure and steady leadership that has enabled our city to remain stable," read an invitation to what became known as Frank's Fat Cat Festival for campaign donors in 2017. "He continues to be the leader that Cleveland needs to maintain the positive momentum created by the public and private sectors working cooperatively."

But this "stability" — which refers primarily to investment conditions — just means more of "it is what it is" for the marginalized poor and working people of Cleveland, whose lives depend on government action on issues like gun violence, bus routes, living wages, affordable housing and lead. That's why there's so much anger in the community over the lately announced Lead Safe Coalition, the pronouncements from which a Plain Dealer Sunday editorial called "laudably strong," despite the fact that the coalition lacks a timeline and an "overall plan of action with clear metrics and cost estimates."

This public-private partnership (an axiomatic public good) is obviously "far wiser" than the "hasty" and "potentially ill-crafted" ballot measure that the citizen advocacy group CLASH is pushing for. The editorial doesn't bother to note that a version of the CLASH legislation was crafted with the input of multiple groups and presented to council in 2017 but never received a hearing because it was backed by the wrong councilman (Jeff Johnson, who was running against Jackson in 2017). The editorial does concede that CLASH's impatience is "understandable." But citizens can now rest easy:

"Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson rightly calls the new coalition's joint commitment to move the needle on lead poisoning a major step forward," the editorial read.

A major step forward? This coalition certainly could "move the needle," whatever that means, in eight or nine years. But the first point in its 5-point plan is to "garner public input and establish a community-wide goal and timeline," work which the city has ostensibly been doing for at least the past year, and which leaders have publicly acknowledged they should have been doing many, many years prior to that. This is classic Jackson. After years of silence and prevent-defense-style leadership, there's a press conference with a lot of faces and minimal information, the impetus for which was undoubtedly CLASH's announced intentions for a ballot initiative. The press conference was a mere week after CLASH issued a press release outlining its plan.

But returning to Square 1, in the words of our fearless local daily, is "a major step forward."

We recall that there's nothing our elected leaders, and the enlightened opinion-makers of the PD editorial board, regard with more disdain than actual democracy. Once again, we are told to have faith in the holy communion of public and private leaders — leaders who in this instance have accomplished nothing more than standing together on a stage. The citizens' group CLASH, and the Cleveland Lead Safe Network (CLSN), which helped draft the 2017 legislation alongside Legal Aid, both of which forced public officials to act (or at least gather en masse for a photo op), had better step aside and let the real leaders lead. There is no celebration of their concerted work on this issue, nor any acknowledgement of the connection between the ballot initiative and the coalition's assembly.

Ballot initiatives, by local definition, are universally bad. They are the ill-crafted works of benighted masses who don't know what's good for them, or else from meddling outsiders who don't have the city's interests at heart. The PD editorial board used similar disparaging language in its condemnation of those who sought referendum on the Q Deal — "Leave aside the small-minded grousing," we were told — and in its belittling of those who supported a constitutional amendment for drug sentencing reform. It was an amendment of almost 2,000 words, the PD said, "an amendment few Ohioans will find the time to read or have the knowledge to interpret." Efforts by the citizenry to recall candidates, even in egregious cases of malfeasance, are likewise regarded as stupid nuisances by those in power. Instead of reviewing why constituents might be unhappy with an elected leader's performance, the preference is to restrict democracy, to make recall more complicated — just as the state of Ohio moved to make constitutional amendments more difficult in the wake of Issue 1.

Those who wish to recall Jackson have a right to be fed up. And though the current recall effort is unlikely to be successful, judging by recent attempts, residents committed to the city's improvement should be thinking seriously about whom they want to support in 2021 and how best to support them. The timid councilpeople eyeing mayoral campaigns, and waiting for blessings by His Snoozing Highness, would be wise to recall one of Jackson's own favorite bits of advice, from former city council president George Forbes: In Cleveland, power isn't given, it's snatched.