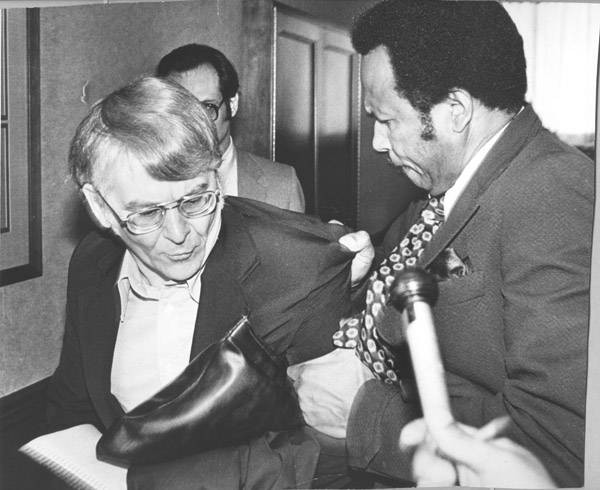

One of the most striking and oft-cited photos in the annals of Cleveland journalism is a 1981 shot, snapped by Cleveland Press photographer Tim Culek, of city council president George Forbes grabbing maverick journalist Roldo Bartimole by the jacket and muscling him out of a council meeting.

The photo was taken not at city hall but at the Bond Court Hotel (later the Sheraton, now the Westin), where Forbes had assembled his council colleagues for a kind of publicity stunt. He'd summoned the press as well, so that they might observe members of council learning about the proposed Sohio Building (later the BP Tower, now the Huntington Bank Building). Roldo warned at the time that the skyscraper on Public Square could be the "most expensive, ill-planned and secrecy-shrouded project since the days when Urban Renewal proved to be Cleveland's disaster."

There was a public portion of the morning meeting, after which Forbes asked the press to leave. But both Roldo, then 47, and newly minted Plain Dealer city hall reporter Gary Clark, refused. In his account of the incident, Roldo wrote that he'd been expecting a security guard to escort them out, but that Forbes "blew his public relations game when he personally tried to evict" them.

Forbes later justified his actions more or less on the grounds that he'd asked nicely.

"I asked him to leave and he wouldn't leave," Forbes told the Free Times in 2000. "I said, 'Roldo, you gotta leave. You can't sit here and eat my grits and then not leave when I ask you to leave.'"

In any case, the physical confrontation captured in the photo — not the meeting itself — is what has accompanied headlines and stories about Roldo Bartimole years after the fact. And it sure accompanied Forbes in 1989, when he unsuccessfully ran for mayor. But Roldo's analysis of the Bond Court proceedings is worth revisiting, as it's representative of the style and tenor of Point of View, the newsletter he self-published for 32 years (1968 to 2000), railing against what his supporters, in 1993, called "Cleveland's bigwig triad: business, politicians and the news media."

The Bond Court Hotel meeting had all three.

"The meeting was advertised as one in which council members would be informed about the Sohio project. In fact, of course, Forbes' intention was nothing of the sort ... .

"Council members instead were at the meeting as props. Forbes needed a forum to make it appear that the council — the elected legislative body of the people of Cleveland — was being informed. And that members were truly being consulted. Ceremonial democracy prevailed instead.

"The media role in such instances is to wait like good little girls and boys for the council members to come out of the meeting, usually one or two at a time as the meeting winds down, and report what they are told. Usually just about all the information had already been leaked to the media by Forbes, blocking back of big business ... .

"Thus the work of dictatorship is usually portrayed as Democratic. This time it didn't quite work out that way."

As the demagogue atop city council, Forbes was long one of Roldo's arch-nemeses. Only a year before the Bond Court kerfuffle, an issue of Point of View was emblazoned with the headline "Resign Now." It called Forbes "a racist, the worst kind," and delineated the ways in which he had manipulated black voters and black council colleagues to his advantage. Its first page concluded in all caps: "THE MAN IS DISGUSTING."

In 1988 and 1989, as Forbes ramped up his failed mayoral campaign, Point of View attacked him regularly, noting Forbes' cozy relationship with the corporate community and the questionable actions of his legal practice. On Oct. 14, 1989, less than a month before the election that Forbes would lose to Mike White, Roldo upbraided him once again: "Forbes apparently believes that he can run on his record as a kick-ass politician. His campaign and demeanor say, 'Fuck you, vote for me.'"

So it's no surprise that Forbes, years later, wasn't as laudatory of Point of View as many other local leaders when retrospectives were penned on the occasion of the newsletter's final issue, in 2000.

"[Roldo's] like a broken clock," Forbes told Cleveland Magazine at the time. "He's right twice a day. He didn't do anything but raise hell with those of us who were trying to do something for this city. I'm telling you, he leaves nothing."

In an interview with the Free Times that year, Forbes elaborated, arguing that Roldo's central flaw was his inflexibility.

"A whole lot of this business is compromise," Forbes said. "And I think that if he had been just a little bit flexible in some of the things he believed in, he would have had a lasting impact."

Roldo is now 85 years old. Since 2015, his work has been published on the local blog, "Have Coffee Will Write," where his readership is vastly diminished from the volatile Kucinich years in the late '70s. Back then, Point of View was distributed to 1,750 subscribers and copied and circulated covertly at many downtown offices. Earlier this year, Roldo wrote a lengthy two-part story chronicling his 50-year career in Cleveland journalism. He did not officially declare his retirement, but the piece was framed as a "summing up," and he admitted his fatigue in multiple conversations with Scene, conversations that left the impression that he'd be producing little new material.

Chris Quinn, editor of Cleveland.com, told Scene that it was hard to believe Roldo was capping his pen.

"I've always felt a comfort knowing Roldo was out there tilting at his windmills," he wrote in an email, "and I think we'll all be the worse for his absence. I don't know that we'll see anyone like him again."

Quinn said he'd always admired Roldo for his zeal and his motives, and had high praise for the way he went after the media, reserving his harshest criticisms for those at the top, not "fellow working journalists."

But he tempered that praise with an acknowledgement of Roldo's polemical style.

"The kind of ranting Roldo did, while entertaining and provocative, harms credibility," Quinn said. "That's fine for someone working for the alternative media, which by its nature attacks the mainstream and the status quo, but reporters seeking to make long-term improvements to the community would not have much success using Roldo's tactics."

That's an echo of former county commissioner Tim Hagan, who, in 2000, compared Roldo unfavorably to the great American muckraker I.F. Stone.

"[Roldo] really wasn't a member of the press. He was an advocate of his point of view," Hagan said. "I don't know that any of Roldo's diatribes ended up with anybody being indicted the way Stone's did."

Maybe not. Although the indictments Roldo pursued were seldom criminal.

***

As a journalist, Roldo's mission was always one of de-mythology. He has been portrayed as an iconoclast, someone who not only attacked but reveled in the attack of regional sacred cows: the foundations, the museums, the "civic leaders," the sports team owners, the press. And though Roldo lately admitted that his unwillingness to compromise made for a more fun and more rewarding career, his reporting was driven by core beliefs about society; namely, that institutions are accorded too much reverence, in fact automatic reverence, and that that reverence impedes honest reporting.

In late 1968, during a tense talk he gave at the City Club, he said almost exactly that:

"When was the last time you saw anywhere a critique of such Cleveland institutions as the Businessmen's Interracial Committee, the Cleveland Development Foundation, the Greater Cleveland Growth Association, the Greater Cleveland Associated Foundations, the PACE Association, the PATH Association, the Cleveland Board of Education, the Citizens League, the United Appeal, University Circle Foundation, Group 66?" Roldo asked a sneering lunch crowd.

"Some of these organizations have immense power over what happens in Cleveland. And they themselves claim to be heavily involved in the life of the city. These institutions have to be demythologized. They are not basically and inherently good. And their motives don't necessarily have to be good, and certainly they must be open to question. Are we afraid to ask those questions publicly?"

Roldo wasn't. After short stints at both the Plain Dealer and the Cleveland bureau of the Wall Street Journal, in whose employ he covered poverty and the city's blundering urban renewal efforts (and with whose image-conscious editors he consistently clashed) he began Point of View, his life's great crusade. His City Club invitation, in fact, was in direct response to a piece he had published in Point of View's 11th issue: "City Club Forum Freedom of Prattle."

In it, he excoriated the City Club for its "debasement of free speech." He insulted its members for "planted and stupid" questions. He wondered how the City Club could consider itself a "bastion of free speech" when, among other things, women were barred from membership.

"As an institution that is revered in the mass media here, it sets a tone for the city," Roldo argued. "Free expression becomes measured by it. Thus, the tone of expression in Cleveland is dull, pretentious and stifling. At a time when issues of great importance threaten to engulf this and other communities, the City Club forums deal in personalities, not issues ... . The City Club has exchanged free speech for free propaganda."

Propaganda is a word that appears repeatedly in Roldo's work, in the pages of Point of View and later, in local alternative weeklies and online blogs. Some of his most venomous screeds exposed the lengths to which the mainstream media — especially Roldo's great nemesis, the "Pee Dee" — shaped discourse via overwhelmingly positive coverage, superficial coverage, or what he regarded as trivial fluff: sports and rock and roll.

"I have watched this past summer, fall and into winter one of the most disgusting displays of slanted, biased, propagandistic, chauvinistic and down-right bad journalism I'd ever expect from a newspaper that I already have the lowest expectations," Roldo wrote in 1996, in the aftermath of the Browns' announced move to Baltimore. "It's a mind-fucking perpetrated by those supposed objective informers of a community who are really so tightly connected to the powers that be ... that they become the public relations apparatus for private interests."

Raging over propaganda has been a constant. In 2004, when inducted into the Cleveland Press Club Hall of Fame, Roldo explained why he felt the act of identifying and criticizing the prevailing orthodoxies was so important. He said, first of all, that he picked on the Plain Dealer so often because "it's the biggest and it's the media leader."

"I believe more effort is devoted by the Plain Dealer to its food pages, its sports pages and its social pages than its coverage of who is doing what to whom in our real world," he said. "The community needs dissent. It must be nurtured. I think it's the responsibility of the news media to foster debate. But there needs to be critical reporting on big institutions for that to happen."

Roldo's unrelenting criticism led leaders to wave him off: He was regarded by many as a contrarian blinkered by his world view, and who therefore only saw the negative.

As if to prove a point, in 1968, a City Club member asked whether or not Roldo could name anything that the media or the government was doing that met his approval. Roldo denied that he should have to.

"You can always find something going on that's good," he said. "And I don't think we ought to spend our time saying what's good when there's so much that's wrong. I don't care whether the media does something nice ... I don't think there's any meaning in pointing out what's good about the media because if they're doing their job, they're supposed to do it."

Fifty years later, this February, when Ideastream reporter Nick Castele asked Roldo if there was anything in Cleveland about which he was hopeful, Roldo's opinion hadn't much changed.

"That's not my job," he said. "My job is to point out, in my opinion, what's wrong. Because that's not being done enough."

***

In assessing Roldo's "lasting impact", downplayed by those he covered critically, one must consider a vital factor. It's something that's seldom mentioned in local profiles and commentaries on his singular career: his role as a mentor to young journalists.

In Michael Roberts' 2000 profile of Roldo for Cleveland Magazine, former Wall Street Journal reporter Greg Stricharchuk said that the example Roldo set was one of his most significant contributions.

"Roldo lifted the consciousness of the reporters in Cleveland about the role of foundations, charities and other organizations that no one paid any attention to," he said. "And he shared information and his experience. Most people in this business don't do that."

Many current local journalists agree. Already, the length of his career and the persistence of his ardor have made him something of a folk hero — even among millennials who would have been too young to read him in his heyday. But more than that, his accessibility and his active engagement with the region's news reporters is unique.

Ideastream's Nick Castele told Scene that he was "late to Roldo," having first encountered his work in an essay that appeared in the Rust Belt Chic anthology. But in 2013, Roldo emailed him with a list of public subsidies that had been awarded to downtown projects and asked if he'd like to have a cup of coffee.

"When we met," Castele said, "he gave me a manila envelope. Inside were a photocopy of an old sin tax ad and two issues of Point of View. One was headlined, "Who Really Governs?" The other, "Don't read all about it!", was a critique of local media.

"Because of Roldo, I've made a point of paying close attention to the ins and outs of Northeast Ohio's public financing arrangements for stadiums. I've also tried my best to keep an eye on campaign contributions."

Eric Sandy worked for Scene for five years before his departure earlier this year. He, too, said that Roldo reached out to him with old copies of Point of View, which he read with relish.

"His style was the forebear of alternative news media," Sandy said. "He used visceral prose and hard, well-researched data to tell a detailed story of what was happening in Cleveland ... Roldo evinced, to me, the grand edict of journalism: Afflict the comfortable. Comfort the afflicted."

Sandy's appreciation was an echo of others': that Roldo's printed rage was earned by his reporting. He wasn't merely serving up hot takes like a later generation of bloggers. His point of view was supported by the documents he obtained, by the alliances he unearthed at the county recorder's office, by the conversations he overheard hanging around city hall.

As to Roldo's long-term impact, Sandy said it's difficult to measure.

"I think city leaders are content to keep his reporting out of sight and out of mind. He's made fools of anyone willing to hold public office in Cleveland by shedding light on decades of corrupt deal-making, myopic policy-making and wanton greed. Will those who write the history books look kindly on Roldo? I don't know. Will I keep his example in mind when I duck into the voting booth, or when I write a story, or when I hire a writer? Of course. And I know I'm not alone."

Another Scene alum, Kyle Swenson, now a reporter at the Washington Post, said that Cleveland ought to erect a statue of Roldo on Lakeside Avenue, "so city hall always remembers someone is watching."

"This is a tough job," Swenson said. "Bad pay. Long hours. And then there's the relentless sense you are working uphill against people — better pay, less hours — who hate what you do and wish you weren't there. That's hard enough when you have a newspaper or station behind you. Roldo pushed against all of them — the city hall flunkies and lazy cops and greedy biz folk — all on his own. For decades. That's true faith in the importance of muckraking."

Michelle Jarboe has been a reporter at the PD for more than a decade. Not originally from Cleveland, she had been unfamiliar with Roldo's work at first. But like many of her colleagues, she received messages from him — by email and snail mail — that were often in sharp contrast to his published hostility toward her employer.

"Though he frequently unleashed scathing criticisms of The Plain Dealer in public forums, his emails to me have been very measured and, often, encouraging," Jarboe wrote Scene in an email. "I've appreciated his critiques of my work. And it brightens my day to open my inbox and find an approving email from Roldo about something I've written ... He riled people up, made readers think and — at least in my experience — pushed younger journalists to do their jobs better. We all should hope to accomplish so much."

Henry Gomez thought so too. He was a business and city hall reporter for the Plain Dealer (2005 to 2009) and then the senior political writer at Cleveland.com until last year when he joined BuzzFeed. He said Roldo was "like that source you have who tells you that you're missing the real story — dig deeper."

"My reporting wouldn't always lead me to the same conclusions that Roldo drew," Gomez said, "but I think it's fair to say that the attention he gave certain issues challenged me to learn new things and ask more questions."

Gomez said that "many times" he'd get calls and notes from Roldo about his coverage at city hall. "I always enjoyed these conversations," he said. "I value Roldo's institutional memory. He was kind enough over my years at the PD to send me back issues of Point of View that he thought would be a resource — and I just devoured them."

Gomez said that many of the institutions Roldo wrote most passionately against really haven't changed much, certainly not in ways he would have preferred.

"I'm not sure if this is the only measure of impact, though," Gomez said. "I think those of us who have taken away something positive from Roldo speak to the fact that what he did has lasting value."

Cleveland.com's Metro columnist Mark Naymik, an alt-weekly alum, said the "obvious takeaway" from his personal interactions with Roldo, and from Roldo's work generally, "is the importance of poking those in power."

The PD's Rachel Dissell knows a thing or two about poking the powerful. She told Scene that Roldo has reached out to her periodically with links to his past work, often to provide context and history to issues she was tackling. And while she confessed she didn't know him well personally, she felt "his instinct to share what he knows speaks to the depths to which he cares about the topics he's raised."

Responding to Forbes' quote, that all Roldo did was "raise hell," Dissell rejoined that we're still talking about him — stories are being written about him — which ought to serve as testimony.

"The motto I live by is 'Question Authority,' so I like to think of myself in the mold of a hell raiser," she said, "even if the way I go about journalism involves less full-throated criticism of elected officials and business leaders and more a hard look at broken systems as a way to spur change."

Gary Clark was the Plain Dealer reporter sitting next to Roldo at the Bond Court Hotel in 1981. He went on to serve as the paper's managing editor before being axed in 2000 and moving to Denver. He highlighted another critical aspect of Roldo's worldview. In addition to his shoe-leather reporting — following the money, checking records, developing sources — "his stories were steeped in a concern for the powerless and contempt of the powerful."

He said Forbes was wrong to trivialize Roldo's impact.

"[He] introduced Cleveland reporters to how things got done in Cleveland, and they went on to better inform the public," Clark said. "He taught them to follow the money and to explore those interlocking relationships. In doing so, Roldo improved the depth and quality of journalism in Cleveland, especially how the powerful use city hall to advance their interests."

That Roldo sacrificed much to retain his editorial independence throughout his career is well known. Other stories have described his sometimes precarious financial position, and a succession of health problems, during Point of View's run. Despite the occasional hardship, Roldo was famously paranoid about accepting gifts that might be perceived as compromising his ethics. He once refused to accept $1,600 that had been raised to support him after a heart attack because he didn't know who'd all contributed to the fund. It goes without saying that he would never eat a meal paid for by a public official.

And so when asked about his legacy, and those who believed his tactics undercut his impact, Roldo merely referenced the stubbornness of his Italian ancestors. He was eager, however, to correct a misrepresentation.

When George Forbes defended throwing Roldo out of the Bond Court Hotel in 1981, he insinuated to the Free Times that Roldo had been freeloading. "You can't sit here and eat my grits and then not leave when I ask you to leave," Forbes said he told Roldo.

"He's wrong," Roldo said. "The breakfast hadn't started."