This is part two of a three-part series looking at the state of water affordability in Cleveland, Philadelphia and beyond, authored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative in partnership with Resolve Philly in Philadelphia. You can find Part 1 here.

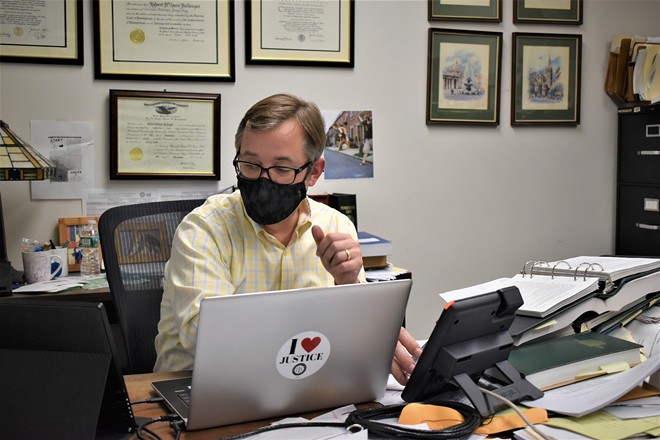

Robert Ballenger’s office in Center City Philadelphia is filled to the brim with stacks of paperwork. It’s just one small sign of the complexity of the assistance programs his low-income clients need.

Ballenger, an attorney who deals with utility issues at the nonprofit Community Legal Services, has helped dozens of people apply for Philadelphia’s Tiered Assistance Program (TAP), which provides residents with low incomes a major discount on their water bills.

But without advocates like Ballenger’s help, it’s not necessarily easy for people to apply for – and stay on – the program.

That’s what Marguerite Penn ran into. Penn, a 59-year-old South Philadelphia resident who survived colon cancer, lives in her mother’s home. Her mom died in 2010, leaving $3,000 in water debt attached to the property. At the time, the narrow rowhouse wasn’t much to look at, with peeling paint and a leaky roof, but it was home.

Penn’s been judiciously fixing the home, slowly saving the money she receives from the government for taking care of her blind cousin. She wants it to be a gathering place for her family; her grandchildren often stop by after school, and she hosted a Thanksgiving dinner at the home last year.

Penn has been able to pay her own water bill – upwards of $100 a month – for years, but could never make a dent in her mom’s debt, which had ballooned to $6,000 due to interest. Eventually, the city sent her a disconnection notice because of that bill.

“I could put maybe $20 dollars on her bill. By the time I pay my bills, I don’t have nothing to put on her (mother’s) bill,” she said.

Penn tried to apply for the TAP program twice, but kept getting rejected for not having all of the proper paperwork sent in in a timely manner.

“They only give you a certain amount of time to do it all, and I had to get all of my information together, (including) my daughter’s paystubs,” she said.

The third time ended up being the charm, but only after getting help from Joan Motz, a Community Legal Services attorney who works with Ballenger, who followed up with the city.

The city requires customers to provide a lot of documents, including two forms of proof they live in their home and 12 months’ income for every adult in the household. Ballenger said the city did streamline that process recently. It now encompasses several other discount programs, allowing people to apply for multiple forms of assistance at once, which Ballenger called a step in the right direction.

Adding to complications for TAP customers: they need to re-enroll every year, meaning they’ve got to dig up documents to prove they’re eligible each year. In 2019, for example, there were almost 8,100 TAP customers who defaulted from the program for failing to re-certify, according to data presented during a presentation to the Philadelphia Rate Board by public advocate Roger Colton.

“A miniscule number of them (TAP customers) exited the programs because they were no longer income-eligible,” Ballenger said. “They were exiting the program because of the required documentation: either they couldn’t produce it or it wasn’t satisfactory to the city.”

Plus, some people are just missing out on the program because the water bill isn’t in their own name, which is a program requirement. Ballenger said those renters can get their landlord’s permission, but the onus is on the tenant to do that.

“That’s a lost opportunity to deliver affordability to a group of users of the system who historically are the most vulnerable,” Ballenger said.

What Cleveland’s doing right

Most large public water and sewer utilities across the country have some form of a discount program to help people afford their bills. But it’s challenging to compare them because each utility runs its own version, and there’s no national database of information on them, said Manny Teodoro, an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Teodoro has researched water and sewer equity and affordability programs for more than a decade, and works directly as a consultant with some cities’ utility departments.

Teodoro said discount and assistance programs for utility bills, like TAP, are often mired in “administrative burdens” – roadblocks that people face to obtain public benefits, like TAP’s paperwork requirements.

Cleveland does have a rare example of a water-discount program that puts up fewer barriers for people to apply. The Homestead Water and Homestead Sewer programs operated, respectively, by Cleveland Water and the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District (NEORSD) provide reduced water and sewer rates for people earning $34,500 or less who are 65 years or older or are permanently disabled.

Unlike with Cleveland’s mainstay Water/Sewer Affordability discount programs, Homestead applicants are only required to fill out a single application; no additional documentation is needed, besides a doctor’s note affirming the applicant has a disability.

The Homestead programs also have a far higher rate of participation than the Water or Sewer Affordability programs, with almost 20,000 people participating in them as of 2019, NEORSD spokesperson Jenn Elting said. That’s almost 61% of the eligible population, which Teodoro said is “higher than usual” for municipal water affordability programs. However, there is a trade-off, Teodoro said: programs requiring fewer documents and thus less proof could open up the potential for fraud, or allegations of fraud from political opponents.

TAP, meanwhile, only has a participation rate of about 25%, or 15,000 out of 60,000 eligible customers.

Cleveland’s water rate structure is also more favorable for people with low incomes than Philadelphia’s, Teodoro said. Cleveland has an “incline” block rate, meaning prices are cheaper initially and increase with use, so people who use less water to save money are rewarded for doing so. Philadelphia’s is the reverse, a “decline” block rate, so the first few units of water you use are more expensive, and the rate declines from there.

Where can both cities look?

Teodoro said he’s not enamored with Philadelphia’s program, compared to other cities he’s examined, based on some still-in-progress analysis. For one, the cost to implement and continue running such a program is immense, something only a large municipality like Philadelphia could even take on.

Meanwhile, because relatively few customers are using the program, that means there are plenty of people with low incomes not participating who are actually paying increased rates to subsidize its continued operation.

“So what you end up with is the poor subsidizing the poor,” he said.

Still, as previously explored in this series, that “rider” that all city of Philadelphia customers pay to subsidize the program isn’t much, about $8 per year per-customer as of 2021.

Regardless, Teodoro said discount programs like TAP should only ever be one part of the solution to deal with the issue of affordability.

True affordability comes from several factors, starting with a water utility’s rate structure, Teodoro argued.

Meanwhile, there’s an important final criteria for affordability: clean, quality water that people can trust over bottled water. Water and sewer infrastructure is expensive, and utilities need to keep up with maintenance in order to provide clean water without interruption.

“If the river is on fire, you ain’t got affordable water, it doesn’t matter how low your bill is,” Teodoro said. “We can’t ever skimp on investment in these systems in the name of affordability.”

After about $1.5 billion of infrastructure investment over the last 20 years, Cleveland is not facing the same “looming water infrastructure problems faced by many large cities around the U.S” and does have high-quality water flowing from its taps, according to a copy of a recent rate study completed for Cleveland Water.

But still, there are a great many people in Cleveland and Philadelphia who are struggling with their utility bills and not participating in any discount program that they are eligible for.

Teodoro pointed to San Antonio as an example of a city that is doing things right with almost 50% of eligible people participating in its discount program.

This story is a part of the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative’s Making Ends Meet project, and a continuing effort to report on the burden of water bills on low-income Clevelanders. NEO SoJo is composed of 18-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets. Conor Morris is a corps member with Report for America. Email him at [email protected].