Music Box Supper Club To Host WMMS Anniversary Event on April 11

A flea market will precede a Cleveland Stories Dinner Party event

By Jeff Niesel on Wed, Mar 27, 2024 at 2:08 pm

[

{

"name": "Ad - NativeInline - Injected",

"component": "38482495",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "5"

},{

"name": "Real 1 Player (r2) - Inline",

"component": "38482494",

"insertPoint": "2/3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "9"

}

]

WMMS, the local FM rock station that was so influential in the '70s and '80s, recently had its famous mascot the Buzzard turn 50. To mark the occasion, Music Box Supper Club will host a special Cleveland Stories Dinner Parties event on Thursday, April 11, featuring a flea market with Buzzard artwork and WMMS memorabilia from the collections of Dave Helton and John Gorman.

The Buzzard Flea Market will run from 3 to 5 p.m., and the storytelling event takes place at 7 p.m. Tickets aren't required for the flea market, but people with reservations for the storytellers part of the night will be the only ones allowed to stay for the discussion featuring Gorman, Helton and former program director Denny Sanders.

Gorman and Sanders, who both still live in the Cleveland area, recently spoke about the station's glory days over coffee and pastries at 5 Points Coffee & Tea in Kamm's Corners.

John and Denny, you both worked together at the station in the 1970s and into the 1980s. What was the key to turning it into one of the most influential stations in the country?

Sanders: One of the things that made WMMS important was that we were willing to add bands and performers that practically no other station would add, and we made them pretty big in Cleveland. Suzi Quatro, who couldn’t get arrested in any other city, was a star in Cleveland. Alex Harvey was a star in Cleveland. Artful Dodger and others were ones that we played that few if any other commercial radio stations played. Then, some other stations in other cities would play them based on our reporting.

Gorman: In those days, Music business decision makers at radio, retail and the labels would look at the trades and see what other stations were playing. Many would initially look at the WMMS list and say, “Who is Roxy Music?” The method behind the madness is that Denny and I were trying to become an important station not only locally but nationally. Our intent was to find new music and break it. Rush is a good example. People started asking, “Who is this Rush band?” We started playing them, and the record labels started coming to us and asking why to get insight on why this new music was breaking out of Greater Clevealnd. The other thing is that we used to have a subscription to New Music Express and Melody Maker magazines. There were copies for everyone to read. That’s how we found out about Suzi Quatro, who was actually from Detroit.

Talk about the station's format or lack thereof.

Sanders: WMMS was not a typical AOR radio station. We played reggae and the Average White Band and the Ronettes and all kinds of material that we thought our audience would enjoy. We weren’t boxed-in by some restrictive designation.

Gorman: in the early days of album radio, there was a defiance toward Top 40 radio. They would not play anything Top 40 would play. We looked at it differently. We thought, “What we have to do is get that high school senior, and that’s the age when they’re growing out of their teenage years but still like the music they grew up with.” We thought of WMMS as their musical graduation. It was like the first time you had a beer or lost your virginity.

The loose approach to format eventually came to an end, didn't it?

Sanders: What damaged the radio station in 1986 was that [owner] Malrite became big enough that they decided they needed a national program director to oversee the programming on all the Malrite stations in all the cities. They brought in this guy who was a hack. He said, “Your format doesn’t make any sense.” He said, “One minute, you play Bruce Springsteen, and then the Isley Brothers, and then it’s the Pretenders, then Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels, and then the Temptations, the Shangri-Las and Prince.” He said, “You’re an AOR station.” I said, “We’re not an AOR station.” I said, “We’re WMMS. That’s the difference.” What happened was that he insisted the station fall into one of these restrictive format designations. What made us famous was that we never fell into a slot. When John and I left, they changed the format to a standard AOR format, and the numbers went down the toilet. At the height of the time we were there, WMMS had a cumulative audience of over 700,000 people. The number one station in Cleveland today, which is generally WMJI, cumes about 450,000. WMMS is currently just under 200,000.

Gorman: And that’s a bad estimate. The numbers of actual people listening to radio are down over 75 percent in 25 years. Shares are based on existing listeners remaining.

Sanders: WMMS today is essentially a talk and sports play-by-play station. Two or three morning and afternoon talk shows are moderately successful, but introducing and breaking new music is no longer influenced by radio.

Talk about the genesis of the Buzzard logo.

Gorman: It was one afternoon in the first week of December 1973 when the weather in Cleveland turned for the worse. It’s cold and snowy. We were talking about the horrible mushroom logo we had. It was the only image of the station. The company wouldn’t give us money for marketing and promotion. We thought we should look at it as a sports team. Instead of athletes, we had on-air personalities. From there, it came down to the idea of having a station mascot. Keep in mind that Cleveland was in terrible shape. I was new to Cleveland. People would hear me speak in a Boston accent and ask why I moved here – as if it was a terrible decision. Denny clued me into the good parts of Cleveland. There was a lakefront and an incredible park system. I thought Greater Cleveland was a diamond in the rough. Our discussion turned to getting a new station logo. That night I was leaving the station.T he afternoon Cleveland Press was delivered to the station around that time we were ending our discussion and the front page had a story about how another Fortune 500 company planned to move out of Cleveland. even though they hadn’t chosen a new location yet. At the time, I was living in East Cleveland, and WMMS was at 55th and Euclid, where the Agora is now. I lived on Euclid near Green. I had no clue how dangerous the area was becoming . I was driving home, and it was getting dark, and the precipitation was a mix of rain and snow. I had WMMS on and Denny is playing “Desolation Row” by Bob Dylan. It was the perfect soundtrack for a shitty weather night in Cleveland when everyone I had been talking to told me how much they hated the city. I thought about what you see flying over something that’s dying. It wouldn’t be a robin. The next morning, I said, “I think I’ve got it. What about a buzzard?” Denny looked at me and said, “A buzzard?” Then, we started talking about it, and it made sense. But we didn’t have money for an artist.

But then David Helton came to you in an odd way, didn’t he?

Gorman: The National Lampoon Radio Hour lost a sponsor and had to cut the show to half an hour. We didn’t listen to the show [during which that announcement was made] before we played it. The show featured the SNL cast prior to that show’s debut. It was [John] Belushi and [Dan] Akroyd and that cast. We didn’t hear it, but it ended with a statement about how the station was cutting the show to half an hour and that we were censoring them. It was a joke.

Sanders: It was a joke and probably a trick to get some mail to see what kind of response they would get and take it to potential advertisers, but they were wise guys. They came on and said some stations wouldn’t carry the whole show anymore.

Gorman: The next morning, I have all these complaints from listeners. We listened to the tape, and then we heard the ending. I was furious with them. One of the letters that came to the station was in the form of a comic strip. It’s this long-haired guy sitting by this giant radio and smoking a joint. He was saying, “National Lampoon is my favorite show.” The next panel is this giant mushroom crashing on the radio and the third panel is the guy looking at us and pointing. He’s saying, “I really like you guys, but you shouldn’t have censored the National Lampoon Radio Hour.” I looked at the thing and thought we had found our buzzard artist. We looked at the envelope, and the return address is David on West Blvd. I thought, “How are we gonna find this guy?”

How’d you find David?

Sanders: How we found him was that we found out there was a connection at American Greetings. They knew how to get in touch with him. I got ahold of him and said we wanted to make arrangements. He had to be at work, but I pulled an address corner out of my hat and said to meet at West 40th and Lorain. There is no West 40th and Lorain! I showed up, and he was at West 41st and I met him, and he joined the team. John laid out what he was looking for. It was a graveyard and there were three tombstones [for WMMS’s competitors].

Gorman: And in those days advertisers didn’t mention competitors. McDonald's never mentioned Burger King. Coke wouldn’t mention Pepsi.

Why do you think the image became so iconic?

Gorman: I think it went beyond the radio station and represented Cleveland, which was its worst enemy. The city, county and state governments were a mess. Fortune 500 companies headquartered here, like Diamond Shamrock, were relocating out of Cleveland. Manufacturing was relocating to the Sunbelt.

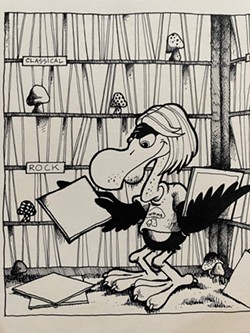

Sanders: David is a helluva an artist At first, the Buzzard was a dirty looking bird, but it became more acceptable and cleaned up later. David did so many wonderful ads. They were all black and white originally and dramatic and people saw the buzzard in all these different scenarios. He was at the beach. He was going to a concert, skiing and doing everything that our listeners were doing,

Gorman: The Buzzard was not only our mascot, but it could be one of our listeners. The Buzzard represented the entire station – but he also represented our listeners.

Sanders: Exactly. You can’t animate a mushroom. It’s very difficult to animate a vegetable.

Gorman: We even had one ad that showed a Buzzard orgy with feathers flying everywhere. The caption was “when you don’t want to get up to change the record.”

Sanders: That one didn’t get published.

Gorman: We had one where the Buzzard was driving a bunch people in a car with the Buzzard driving. We had one where the Buzzard was driving a bunch of hippies in the car. In another one, the Buzzard was picking up a girl hitchhiker who was hitchhiking. The more we did it, the more we realized what we could with it.

And your audience embraced the character.

Sanders: Yes. We would see people with shirts they made themselves. We had more than one person who had a Buzzard tattoo. It was a fabulous character, and our listeners embraced him completely..

Gorman: It had a life of its own.

Sanders: The character became ubiquitous. People loved it. It was part of the great marketing of the radio station. We finally got a little bit of money for some television advertising. There were syndicated ads you could buy. We didn’t want any of that. We wanted everything to be unique. David and Mark Spangler had a side company. They made an animated Buzzard commercial and did it by hand. That was our first advertising. It was so different from any other station. When our competitors advertised, they took one of the off the shelf generics. [Helton and Spangler] created a cartoon spot from scratch that featured the Buzzard, and it was wonderful.

Gorman: Most of them those original ads are on YouTube. They’re primitive – like a '30s cartoon, which was our intent, and many have a Cleveland background. We were adamant at the station that when cable started showing up, and you would get other stations like ESPN and stations out of Chicago and New York. You’d see an ad that WGAR or WGCL would run in Cleveland, and you’d see the identical ad in New York with the call letters for that station. We wanted everything coming out of WMMS to be in house, homegrown.

The Coffee Break Concerts were a huge hit. What were some of your favorite ones?

Gorman: There are so many. Bryan Adams is a good example. He played before he broke nationally. The first album came out and he credited the Coffee Break Concerts with giving him the exposure that other stations didn’t give him. The next year, his next album and he called us and asked to bring Bob Clearmountain to produce his concert here. He was one of the great rock producers at the time.

Sanders: Bryan Adams, Cyndi Lauper and Warren Zevon played Coffee Breaks when they were just getting started. Foghat. Peter Frampton. Local bands like The Generators. And, of course, the Michael Stanley Band.

Sanders: Lou Reed did one. That was in 1983. He visited the station in the mid-1970s and was a real jerk. He had just dyed his hair blonde. [DJ Kid] Leo had a great opening line. He said, “Hey Lou, do blondes have more fun?” And Lou said, “How long have you been an asshole?” And that was the end of the interview. But by the time he did the Coffee Break in 1983, he was cooperative. He may have been running out of money or maybe just grew up by that time, so he behaved himself.

What do you think of commercial radio today?

Sanders: When we were riding at WMMS, there were maybe 14 different owners of radio stations in Cleveland. Today, there are four, one of which is religious. When you go from 14 different owners to essentially three. The point is that the talent and the local programmers don't have much power anymore. When the huge companies own hundreds of stations, they standardize them. When they do that, they make them common, and they’re nothing unique to their region. It is like Wal-Mart. They all look pretty much the same regardless of what city they are in. It’s an off-the-shelf generic format. People creating the material have no negotiating power. In the old days, if you didn’t like where you worked, you would go across the street. Now, you can't do that. They own everything. Since they essentially took the music selection away from the local crew, regionalism dried up. Today, if you look at the ratings of the top stations in Cleveland, they’re all older demographics. The three stations which emphasize contemporary music are down toward the bottom of the ratings. The reason is simple. They’re not playing the music that young people want. They’re not in touch with them.

Gorman: And payola is legal now too. Labels and management often cut deals to get airplay and rotation on stations. The year Madonna played the Superbowl, iHeart offered a menu of featuring airplay , website exposure and formats available that went public. No one was surprised.

Sanders: National standardization ruined rock ’n’ roll radio. It took the power of the music selection and the programming away from the locals and replaced it with some kind of nation-wide generic approach, which was common and had no real appeal.

Gorman: They’ve cut costs, but they’re all in bankruptcy. You can’t fool the public. If they don’t hear what they want from a radio station, they will go other places — and have.

Sanders: I have three kids and none of them own a radio. They don’t listen to it. The music section was taken away from the local music people and given to some guy nationally. What the hell does he know about these unique cities? All he knows is who’s paying for it and what’s good for advertising.

Talk about what the upcoming event at the Music Box will be like.

Gorman: There will be vintage buzzard items for sale. David [Helton] has old vintage WMMS stuff. [Music Box's] Mike Miller knows what questions to ask. It’s whatever he wants to talk about. Here we are 50 years later, and we have people who came up with this idea and made these connections and who worked together for all these years. Here we are still together. We can look back at everything that happened because we lived it and were in the eye of the storm.

Subscribe to Cleveland Scene newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

The Buzzard Flea Market will run from 3 to 5 p.m., and the storytelling event takes place at 7 p.m. Tickets aren't required for the flea market, but people with reservations for the storytellers part of the night will be the only ones allowed to stay for the discussion featuring Gorman, Helton and former program director Denny Sanders.

Gorman and Sanders, who both still live in the Cleveland area, recently spoke about the station's glory days over coffee and pastries at 5 Points Coffee & Tea in Kamm's Corners.

John and Denny, you both worked together at the station in the 1970s and into the 1980s. What was the key to turning it into one of the most influential stations in the country?

Sanders: One of the things that made WMMS important was that we were willing to add bands and performers that practically no other station would add, and we made them pretty big in Cleveland. Suzi Quatro, who couldn’t get arrested in any other city, was a star in Cleveland. Alex Harvey was a star in Cleveland. Artful Dodger and others were ones that we played that few if any other commercial radio stations played. Then, some other stations in other cities would play them based on our reporting.

Gorman: In those days, Music business decision makers at radio, retail and the labels would look at the trades and see what other stations were playing. Many would initially look at the WMMS list and say, “Who is Roxy Music?” The method behind the madness is that Denny and I were trying to become an important station not only locally but nationally. Our intent was to find new music and break it. Rush is a good example. People started asking, “Who is this Rush band?” We started playing them, and the record labels started coming to us and asking why to get insight on why this new music was breaking out of Greater Clevealnd. The other thing is that we used to have a subscription to New Music Express and Melody Maker magazines. There were copies for everyone to read. That’s how we found out about Suzi Quatro, who was actually from Detroit.

Talk about the station's format or lack thereof.

Sanders: WMMS was not a typical AOR radio station. We played reggae and the Average White Band and the Ronettes and all kinds of material that we thought our audience would enjoy. We weren’t boxed-in by some restrictive designation.

Gorman: in the early days of album radio, there was a defiance toward Top 40 radio. They would not play anything Top 40 would play. We looked at it differently. We thought, “What we have to do is get that high school senior, and that’s the age when they’re growing out of their teenage years but still like the music they grew up with.” We thought of WMMS as their musical graduation. It was like the first time you had a beer or lost your virginity.

The loose approach to format eventually came to an end, didn't it?

Sanders: What damaged the radio station in 1986 was that [owner] Malrite became big enough that they decided they needed a national program director to oversee the programming on all the Malrite stations in all the cities. They brought in this guy who was a hack. He said, “Your format doesn’t make any sense.” He said, “One minute, you play Bruce Springsteen, and then the Isley Brothers, and then it’s the Pretenders, then Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels, and then the Temptations, the Shangri-Las and Prince.” He said, “You’re an AOR station.” I said, “We’re not an AOR station.” I said, “We’re WMMS. That’s the difference.” What happened was that he insisted the station fall into one of these restrictive format designations. What made us famous was that we never fell into a slot. When John and I left, they changed the format to a standard AOR format, and the numbers went down the toilet. At the height of the time we were there, WMMS had a cumulative audience of over 700,000 people. The number one station in Cleveland today, which is generally WMJI, cumes about 450,000. WMMS is currently just under 200,000.

Gorman: And that’s a bad estimate. The numbers of actual people listening to radio are down over 75 percent in 25 years. Shares are based on existing listeners remaining.

Sanders: WMMS today is essentially a talk and sports play-by-play station. Two or three morning and afternoon talk shows are moderately successful, but introducing and breaking new music is no longer influenced by radio.

Talk about the genesis of the Buzzard logo.

Gorman: It was one afternoon in the first week of December 1973 when the weather in Cleveland turned for the worse. It’s cold and snowy. We were talking about the horrible mushroom logo we had. It was the only image of the station. The company wouldn’t give us money for marketing and promotion. We thought we should look at it as a sports team. Instead of athletes, we had on-air personalities. From there, it came down to the idea of having a station mascot. Keep in mind that Cleveland was in terrible shape. I was new to Cleveland. People would hear me speak in a Boston accent and ask why I moved here – as if it was a terrible decision. Denny clued me into the good parts of Cleveland. There was a lakefront and an incredible park system. I thought Greater Cleveland was a diamond in the rough. Our discussion turned to getting a new station logo. That night I was leaving the station.T he afternoon Cleveland Press was delivered to the station around that time we were ending our discussion and the front page had a story about how another Fortune 500 company planned to move out of Cleveland. even though they hadn’t chosen a new location yet. At the time, I was living in East Cleveland, and WMMS was at 55th and Euclid, where the Agora is now. I lived on Euclid near Green. I had no clue how dangerous the area was becoming . I was driving home, and it was getting dark, and the precipitation was a mix of rain and snow. I had WMMS on and Denny is playing “Desolation Row” by Bob Dylan. It was the perfect soundtrack for a shitty weather night in Cleveland when everyone I had been talking to told me how much they hated the city. I thought about what you see flying over something that’s dying. It wouldn’t be a robin. The next morning, I said, “I think I’ve got it. What about a buzzard?” Denny looked at me and said, “A buzzard?” Then, we started talking about it, and it made sense. But we didn’t have money for an artist.

But then David Helton came to you in an odd way, didn’t he?

Gorman: The National Lampoon Radio Hour lost a sponsor and had to cut the show to half an hour. We didn’t listen to the show [during which that announcement was made] before we played it. The show featured the SNL cast prior to that show’s debut. It was [John] Belushi and [Dan] Akroyd and that cast. We didn’t hear it, but it ended with a statement about how the station was cutting the show to half an hour and that we were censoring them. It was a joke.

Sanders: It was a joke and probably a trick to get some mail to see what kind of response they would get and take it to potential advertisers, but they were wise guys. They came on and said some stations wouldn’t carry the whole show anymore.

Gorman: The next morning, I have all these complaints from listeners. We listened to the tape, and then we heard the ending. I was furious with them. One of the letters that came to the station was in the form of a comic strip. It’s this long-haired guy sitting by this giant radio and smoking a joint. He was saying, “National Lampoon is my favorite show.” The next panel is this giant mushroom crashing on the radio and the third panel is the guy looking at us and pointing. He’s saying, “I really like you guys, but you shouldn’t have censored the National Lampoon Radio Hour.” I looked at the thing and thought we had found our buzzard artist. We looked at the envelope, and the return address is David on West Blvd. I thought, “How are we gonna find this guy?”

How’d you find David?

Sanders: How we found him was that we found out there was a connection at American Greetings. They knew how to get in touch with him. I got ahold of him and said we wanted to make arrangements. He had to be at work, but I pulled an address corner out of my hat and said to meet at West 40th and Lorain. There is no West 40th and Lorain! I showed up, and he was at West 41st and I met him, and he joined the team. John laid out what he was looking for. It was a graveyard and there were three tombstones [for WMMS’s competitors].

Gorman: And in those days advertisers didn’t mention competitors. McDonald's never mentioned Burger King. Coke wouldn’t mention Pepsi.

Why do you think the image became so iconic?

Gorman: I think it went beyond the radio station and represented Cleveland, which was its worst enemy. The city, county and state governments were a mess. Fortune 500 companies headquartered here, like Diamond Shamrock, were relocating out of Cleveland. Manufacturing was relocating to the Sunbelt.

Sanders: David is a helluva an artist At first, the Buzzard was a dirty looking bird, but it became more acceptable and cleaned up later. David did so many wonderful ads. They were all black and white originally and dramatic and people saw the buzzard in all these different scenarios. He was at the beach. He was going to a concert, skiing and doing everything that our listeners were doing,

Gorman: The Buzzard was not only our mascot, but it could be one of our listeners. The Buzzard represented the entire station – but he also represented our listeners.

Sanders: Exactly. You can’t animate a mushroom. It’s very difficult to animate a vegetable.

Gorman: We even had one ad that showed a Buzzard orgy with feathers flying everywhere. The caption was “when you don’t want to get up to change the record.”

Sanders: That one didn’t get published.

Gorman: We had one where the Buzzard was driving a bunch people in a car with the Buzzard driving. We had one where the Buzzard was driving a bunch of hippies in the car. In another one, the Buzzard was picking up a girl hitchhiker who was hitchhiking. The more we did it, the more we realized what we could with it.

And your audience embraced the character.

Sanders: Yes. We would see people with shirts they made themselves. We had more than one person who had a Buzzard tattoo. It was a fabulous character, and our listeners embraced him completely..

Gorman: It had a life of its own.

Sanders: The character became ubiquitous. People loved it. It was part of the great marketing of the radio station. We finally got a little bit of money for some television advertising. There were syndicated ads you could buy. We didn’t want any of that. We wanted everything to be unique. David and Mark Spangler had a side company. They made an animated Buzzard commercial and did it by hand. That was our first advertising. It was so different from any other station. When our competitors advertised, they took one of the off the shelf generics. [Helton and Spangler] created a cartoon spot from scratch that featured the Buzzard, and it was wonderful.

Gorman: Most of them those original ads are on YouTube. They’re primitive – like a '30s cartoon, which was our intent, and many have a Cleveland background. We were adamant at the station that when cable started showing up, and you would get other stations like ESPN and stations out of Chicago and New York. You’d see an ad that WGAR or WGCL would run in Cleveland, and you’d see the identical ad in New York with the call letters for that station. We wanted everything coming out of WMMS to be in house, homegrown.

The Coffee Break Concerts were a huge hit. What were some of your favorite ones?

Gorman: There are so many. Bryan Adams is a good example. He played before he broke nationally. The first album came out and he credited the Coffee Break Concerts with giving him the exposure that other stations didn’t give him. The next year, his next album and he called us and asked to bring Bob Clearmountain to produce his concert here. He was one of the great rock producers at the time.

Sanders: Bryan Adams, Cyndi Lauper and Warren Zevon played Coffee Breaks when they were just getting started. Foghat. Peter Frampton. Local bands like The Generators. And, of course, the Michael Stanley Band.

Sanders: Lou Reed did one. That was in 1983. He visited the station in the mid-1970s and was a real jerk. He had just dyed his hair blonde. [DJ Kid] Leo had a great opening line. He said, “Hey Lou, do blondes have more fun?” And Lou said, “How long have you been an asshole?” And that was the end of the interview. But by the time he did the Coffee Break in 1983, he was cooperative. He may have been running out of money or maybe just grew up by that time, so he behaved himself.

What do you think of commercial radio today?

Sanders: When we were riding at WMMS, there were maybe 14 different owners of radio stations in Cleveland. Today, there are four, one of which is religious. When you go from 14 different owners to essentially three. The point is that the talent and the local programmers don't have much power anymore. When the huge companies own hundreds of stations, they standardize them. When they do that, they make them common, and they’re nothing unique to their region. It is like Wal-Mart. They all look pretty much the same regardless of what city they are in. It’s an off-the-shelf generic format. People creating the material have no negotiating power. In the old days, if you didn’t like where you worked, you would go across the street. Now, you can't do that. They own everything. Since they essentially took the music selection away from the local crew, regionalism dried up. Today, if you look at the ratings of the top stations in Cleveland, they’re all older demographics. The three stations which emphasize contemporary music are down toward the bottom of the ratings. The reason is simple. They’re not playing the music that young people want. They’re not in touch with them.

Gorman: And payola is legal now too. Labels and management often cut deals to get airplay and rotation on stations. The year Madonna played the Superbowl, iHeart offered a menu of featuring airplay , website exposure and formats available that went public. No one was surprised.

Sanders: National standardization ruined rock ’n’ roll radio. It took the power of the music selection and the programming away from the locals and replaced it with some kind of nation-wide generic approach, which was common and had no real appeal.

Gorman: They’ve cut costs, but they’re all in bankruptcy. You can’t fool the public. If they don’t hear what they want from a radio station, they will go other places — and have.

Sanders: I have three kids and none of them own a radio. They don’t listen to it. The music section was taken away from the local music people and given to some guy nationally. What the hell does he know about these unique cities? All he knows is who’s paying for it and what’s good for advertising.

Talk about what the upcoming event at the Music Box will be like.

Gorman: There will be vintage buzzard items for sale. David [Helton] has old vintage WMMS stuff. [Music Box's] Mike Miller knows what questions to ask. It’s whatever he wants to talk about. Here we are 50 years later, and we have people who came up with this idea and made these connections and who worked together for all these years. Here we are still together. We can look back at everything that happened because we lived it and were in the eye of the storm.

Subscribe to Cleveland Scene newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

SCENE Supporters make it possible to tell the Cleveland stories you won’t find elsewhere.

Become a supporter today.

About The Author

Jeff Niesel

Jeff has been covering the Cleveland music scene for more than 20 years now. And on a regular basis, he tries to talk to whatever big acts are coming through town, too. If you're in a band that he needs to hear, email him at [email protected].

Scroll to read more Local Music articles

Newsletters

Join Cleveland Scene Newsletters

Subscribe now to get the latest news delivered right to your inbox.