It works like this: In addition to the 10-cut key itself (introduced later, in 1995), VATS is an electrical resistor device plopped in the middle of the key. When the key is turned, a computer detects how much of the current dropped through the resistor. If it matches up, the car starts, If it doesn't, there's a three-minute or so delay until you can try again. (The delay was part of the design; GM figured thieves were in a hurry and wouldn't wait around as their chances of being caught went up.) There were 15 codes, though GM discontinued the lowest resistance in 1989 because of technical issues.

The fact that VATS worked at first wasn't surprising, but neither was the eventual discovery of ways to beat the system. Like most security measures, give criminals enough time and they'll figure out a way to hack their way around the roadblocks.

"I had to go to the dealership, I had to see the car, and I had to have the key in my hand," says Ott. "I had this thing the size of a cigarette pack. I can make any key, you know. The hard part is figuring out what key to make. I had a decoder [called an interrogator]. So while the salesman was doing whatever, I'd put it in there and see what VATS code it came back with. Sevens and nines are the most popular ones. You have to buy different key blanks, a bunch of them. You call up the supplier and you say send me 10 No. 2s, 10 No. 4s, etc. So I had all these key blanks.

"They're getting smarter with their keys, putting them in a lock box, so if there's a missing key, they search everywhere high and low for that key," he says. "But that's the big dealerships, not the mom-and-pop shops.

As fobs were introduced, allowing remote unlocking, Ott and others predictably adapted.

"I still had to go to the dealership and clone the fobs," he says. "You have the original one and you have a blank one and you put them together so they mate. The beautiful part was the dealership was always looking for skid marks, like the car was dragged off by a tow truck or something. They had no concept of how cars were being taken."

When it came to evading other security measures, Ott took advantage of your friendly auto mechanic's desire to offer help to the 9-to-5 crowd before they have to be at work.

"A lot of them have gates. You have to wait until 7 a.m. That's when the service department opens, before everyone else gets there," he says. "The service guy opens the door and I'd be the next thing out of there."

Had things gone differently, Ott might have used that intricate knowledge to help dealerships instead of ripping them off.

When he was in federal prison in Lexington, Kentucky, in the early '80s — "If you were going to do time anywhere, you'd want it to be there," he says of the accommodations — he met a guy who'd been sent away for embezzling millions of dollars. They shared stories. He was a smart kid.

"He said, 'What you oughta do is write GM and see if they're interested in hiring you to beef up security.' So he wrote me a letter and I sent it out to GM and Chrysler and Ford," Ott says. "GM sent me a letter back saying to get in touch when I got out, so I did. I went up to Detroit, got cleared by my asshole parole officer to go with a travel permit, showed him the letter. I talked to this guy and he asked how long it would take for me to steal a Chevy or a Cadillac. I told him I took them off lots, that was my forte. He says that's exactly what he's talking about. How do we beef it up?"

So Ott was dispatched to a dealership about a mile down the road. He returned with a car not long after.

"They called the dealership and told them they had the car or whatever, and they offered me $45,000 a year to travel around the country educating dealerships on security," he says. "I came back home and, like three weeks later, I got another letter from GM saying they couldn't use me at this time. I guess the FBI told them whatever information I got I would use against GM."

In a bit of self reflection that's hard to believe some 30-odd years later, Ott says, "It was a good opportunity for me to get a job. My whole life might have been changed."

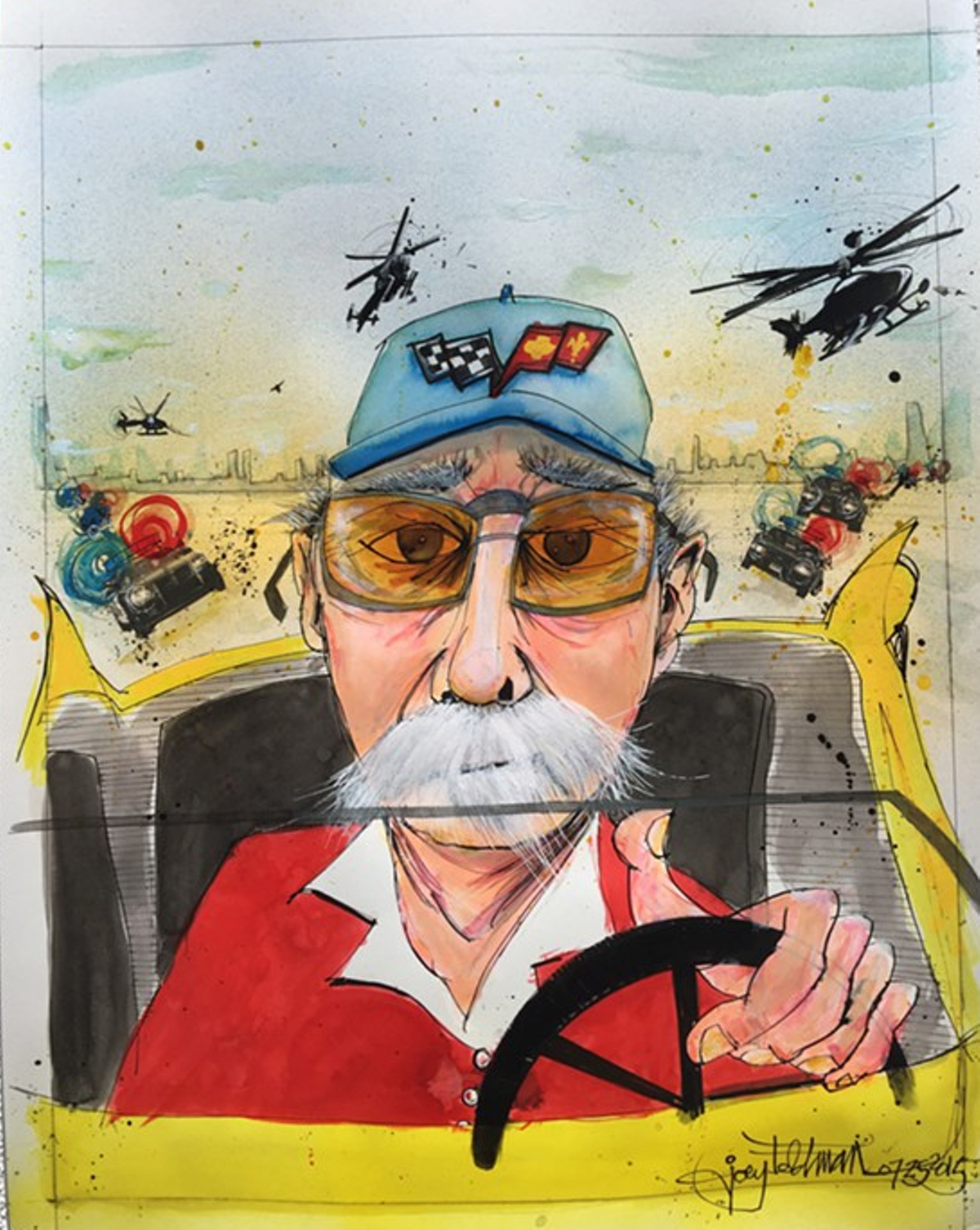

Spend any time with Dan Ott, you hear stories. In his 60 years committing crimes across most of the United States, he's stockpiled more than a few, all of which are hard to believe on one level or another.

"He's lived quite the life," says Paul Mancino, a lawyer who has represented Ott a couple times. Carolyn Kucharski, a federal public defender who represented Ott in his last case, echoed the sentiment.

The stories come pouring out of Ott, sometimes without prompts or segues. They're related in matter-of-fact language, absent emotion or inflection, like a high-schooler relaying to his dad what happened at school that day. What they lack in performance value they more than make up for in drama. They are tall tales, possibly and probably true, most unverifiable. They are part of what makes Dan Ott endearing. As one police officer who's investigated Ott over the years told me, "It was too bad he was a criminal. He would have been a neat guy to have a beer with and talk to."

Ott says at one point he was running heavy construction equipment to a law enforcement official in Sarasota Springs, Florida. He doesn't mention him by name but says the FBI was keenly interested in the officer's off-the-clock habits for reasons like this:

"The guy wanted this painting stolen out of Lucille Ball's house on Bird Key," Ott says. "He says, 'You'll have 20 minutes after the alarm goes off. The call will come and you'll have 20 minutes before anyone goes down. I want that painting.'"

So, Ott says, he and a friend broke in. The painting, incidentally, was of some water and waves, not anything he personally liked, but they took it and some other stuff — "a bunch of nothing, really," says Ott.

There's no record that the I Love Lucy star ever lived in Sarasota, though it's long been rumored. A Sarasota Herald-Tribune gossip columnist first mentioned the idea on Sept. 6, 1971, and the gossip spread over the years from there, to the point that real estate agents have touted the celebrity's name in connection with the address — 22 Seagull Lane — ever since. It's just not true, however. Sarasota Magazine called it the "oldest, most disproven rumor in Sarasota" in a 2012 piece on the property.

Which, of course, doesn't make Ott's story false. The official who dispatched Ott to pilfer the painting could have believed Ball really lived there, after all. A similar streak of unverifiable veracity runs through Ott's other yarns, spun from highways east to west.

"We got Elizabeth Taylor's car," he says. "Stole her car. Her dog was in there, a little tiny dog. I gave the dog to my cousin. We didn't know whose it was at first, but her stuff was in the glovebox. It was a long time ago, late '70s or early '80s. It was in the Sands parking lot." (Without a specific date, the Las Vegas police department said it could neither determine the veracity of the claim nor conduct a search for a possible police report.)

"We got Flip Wilson's car too," Ott says. "He was an entertainer. We got his Mercedes, a red Mercedes. We had a guy drive it back to Cleveland but he got busted in Indiana someplace."

For all the times Ott's name made the papers, there were plenty of other times his exploits were displayed front and center without his name.

"I stole a gold 1970 Cadillac in Berea one time," he says. "I gave it to my wife to drive. I ended up taking it back to the house a year later and put it back in the driveway. I don't know why I did that. I guess just for fun."

He says someone wrote a story about it. It could have been the Plain Dealer or the defunct Cleveland Press or the community newspaper. The same goes for the time he stole a car with a bunch of Bibles in the back. It turned out it belonged to a church group. Someone told the local paper all about it. Ott saw it and dumped the Bibles in a donation bin and called the group and told them where to find them. "'Thief with a heart,' or something like that, was the headline," he says.

And there was the cow.

Ott used to spend weekends at a campground in Northfield, Ohio, by Fell Lake Park, a long since gone family-friendly pool and summer hangout that neighbored Acadia Farms, the 900-acre estate of Cyrus Eaton, at the time one of the richest and most controversial businessmen in America. Eaton, in addition to being a lightning rod for public sentiment by openly advocating for an ease in Cold War relations with Russia, was also an avid rancher. He raised prize-winning Shorthorn cattle, the herd numbering around 300, the largest flock at the time east of the Mississippi. He counted Nikita Khrushchev as a close friend and sent the Soviet premier a prize bull in 1957. Khrushchev returned the favor by sending Eaton three white stallions in 1959.

"One morning me and my cousin were there and this cow's at the fence," says Ott. "And he looks at me and says, 'What's stopping us from stealing a cow?'"

So they stole the cow, figuring it would keep the campground grill filled for the rest of the summer. They took it to a market on East 55th Street, right up to the front door. The butcher, bewildered at the sight of a live animal, told them they had to kill it first. "I don't cut up live cows," the guy said. So they took it to a guy in Richfield who quickly noticed this wasn't your standard beef cow. "That's one strange-looking cow," he said. But the guy killed and skinned it anyway and they took it back to the butcher.

A few weeks later, the gravity of the heist became apparent.

"There was this little four-page paper for the community," he says. "And there was one page, real big, offering a $25,000 reward for the cow. It was some prize-winning cow or something and belonged to Cyrus Eaton. I asked my cousin what we should do. He said we should send him a hamburger."

It's hard not to love the stories, and Ott seems to relish the chance to brag a little, but each story has a victim, whether they're celebrities or regular Joes. One former law enforcement officer who dealt with Ott over three decades says Ott was insistent that he never physically hurt anyone. But he surrounded himself with those who did, and he hurt plenty of people himself in very real ways. That reality seems to be lost on Ott. He cares about many people — his family, his friends — though he admits he's behaved awfully toward both at times. But the part of his soul that should feel compassion for his victims was long ago siphoned off: maybe because it never really existed in the first place and was thus easily disposed of, or because to let it linger would make what he did — what he wanted to do, what he never stopped doing — impossible.

"I took a Camaro out of Brookpark Road one time, New York license plates," he says. "It turned out to be people on their honeymoon. All their clothes were in the trunk, and the box of money from the wedding. I got home and I opened all the envelopes. My wife comes over and asks what I'm doing. I say, 'What does it look like I'm doing?' I told her I found it. She said, 'Those are those people's wedding gifts. You just ruined their lives.' I told her, 'Here's all the cards. Send everyone thank-you notes if you feel that bad about it.' There was like $3,200 in the box. I feel a little bad about it. It probably put a dent in starting their life out."

Steal cars as often and as long as Ott has, and you're bound to get in trouble, no matter your talents. Combine the raw number of thefts — again, north of 1,000 — with the number of people involved in the front and back ends of the business, factor in their skills, abilities and motivation for self preservation should they get pinched, and multiply the chances by the number of jurisdictions and agencies interested in your escapade -— local police, sheriff's offices, the Ohio State Highway Patrol, various task forces, the FBI — and the odds of ending up behind bars are pretty high.

"You never really think about getting arrested," he says. "You're making so much money. There's always the chance. I'm sure I thought about it a little back then. But you think if you get arrested that you'll have a nice little nest egg."

Ott has spent a good many years of his late adult life in prison, though he hasn't always helped his cause by flying below the radar or shying away from authorities. He's instead routinely engaged the men and women with badges in an antagonistic game of cops and robbers that only he seems to enjoy.

For example: Ott first blipped on the FBI's radar in the late '70s, when he stole an FBI surveillance van. There are, naturally, conflicting reports on whether they'd been looking into Ott prior to the theft, but the very real verifiable fact is that sometime around 1977, Ott made off with one of their vehicles.

"There was just a bunch of radios in the back," says Ott. "I didn't really know what they were for, but I figured it was the FBI. I took it down to Mansfield. They wanted to make a case against us because they were pissed about the radio and the van. They were embarrassed. I'm not even supposed to talk about the van anymore."

The surveillance van had been under the purview of FBI agent Keith Thornton, a man who would work Ott's case for the next few years with the help of one of Ott's accomplices.

"One of the guys we were working with was giving all this information to the feds," he says. "We told him, 'We know you're cooperating, just let us know what you told them so we can clean our act up.' So he did and we spent like two days going to different places we had stuff — a farm in Wayne County, a house in Richfield — putting it different places."

Ott lived near Bath, a suburb of Akron, and there was a Holiday Inn up the street where he would drink. He'd also leave the bar's number for people to get in touch with him.

"This barmaid would take messages for me," he says. "I don't want to give them my number. So I go in one night, ask her if there are any messages and she says no. I see this guy and he's staring at me. Never seen him before. He seems awfully interested in me. So I had another drink and he comes over and says, 'Keith Thornton, FBI.' I say, 'Dan Ott, Bath.' That was the first time I met Keith Thornton."

They'd interact on a professional level as Thornton put together the case that would see Ott sentenced to eight years in federal prison. But even when Thornton moved on to the Summit County Sheriff's Department, and even after he retired, Ott was nearby. Literally. He bought a house six doors down from Thornton just so he could "wave at him when he got his mail." They're neighbors to this day.

"I didn't have enough sense to quit aggravating them I guess," says Ott. "I used to screw with them. I'd get in my car to leave the house in the morning and I'd see two cars following me. I'd go down and off ramp and there they were. So I'd drive to all the way to Sandusky and get some ice cream and then go home."

Thornton, unsurprisingly, didn't respond to a request to comment for this story, nor did a roster of other law enforcement officials who investigated Ott over the years, including John Paskin of the National Insurance Crime Bureau, who worked for the Ohio State Highway Patrol during Ott's golden years.