Things would have been different, maybe, if Greg McNeil and his family knew then what they know now. His son, Sam, overdosed on heroin and died at the age of 28 in the fall of 2015.

The McNeils are far from alone in this, both in facing the tragedy of losing a loved one and turning that grief into action. All over Ohio, grieving parents are committing in their own unique way to tackling the great public health crisis of our time.

Almost immediately, the McNeils charted a new course, bottling the lessons they'd learned in their Orphean journey through Sam's years of addiction and sharing them with other families suffering the same numbing, helpless madness.

They began as most do: with the obituary. Theirs was the honest, open version that's becoming more common as the crisis becomes more visible. "Sam was a kind and loving young man whose greatest gift was his huge heart and compassion for others," it read. "Sam died from a drug overdose after losing an 8-year battle with addiction. If one person reads this and it stops them from going down the path of addiction, then his death was not in vain."

There wasn't much of a choice. This didn't have to happen, McNeil says, and so he and his family set up a nonprofit called Cover2 Resources. (Cover 2 is a popular defensive scheme in football, Sam's favorite sport.) They aimed to educate others on everything McNeil didn't know when his son was slowly dying. A natural networker with the gift of sharp conversation, McNeil started drawing the crisis into the open, meeting and interviewing many of the people who are trying to end this new American nightmare.

"I have become, though this journey, spiritual," McNeil says.

We meet on an early spring morning in his conference room in Twinsburg, where he records podcast interviews — 99 to date in a little more than a year — with a range of people involved in every aspect of addiction. His crown of spiked white hair rests atop a face creased with concern.

In conversation, McNeil speaks crisply and with forethought, his arguments layered like sturdy foundations, all tinged with a fatherly instinct to get things done. Those who know him call him a facilitator. "Everyone I know I kind of refer to him," says Dan Meloy, the public safety director of Colerain Township, a sleepy exurb outside of Cincinnati where our story begins.

When McNeil sees something that works, he examines it and promotes it to the audience that needs it. With Cover2's sense of capital-M mission, McNeil has moved far beyond hoping to help one single person. We're past hope and into practice now, because McNeil was instrumental in bringing a novel method for interacting with addicts and preventing deaths to Summit County, a method that's already shown astounding success in Meloy's Colerain Township and one he and others hope will take root in other law enforcement agencies across Northeast Ohio.

***

The crisis has touched every conceivable corner of American life, upending and entire generation, and it's getting worse. Overdoses are now the leadng cause of death for Americans under the age of 50, and the 2016 death toll of about 59,000 surpasses the country's peak number of car deaths (in 1972), the peak number of HIV deaths (in 1995) and the peak number of gun deaths (in 1993).

Committees and task forces and nonprofits are forming en masse. Testimony is being delivered in Washington (most recently by Cuyahoga County Medical Examiner Thomas Gilson, who said that the "opiate crisis is a slow-moving mass fatality event that occurred last year, is occurring again this year and will occur again next year.") And health professionals are convening at the highest levels of government, all working to connect solutions to problems as county morgues literally overflow with bodies. Ohio is at the epicenter of the whole thing.

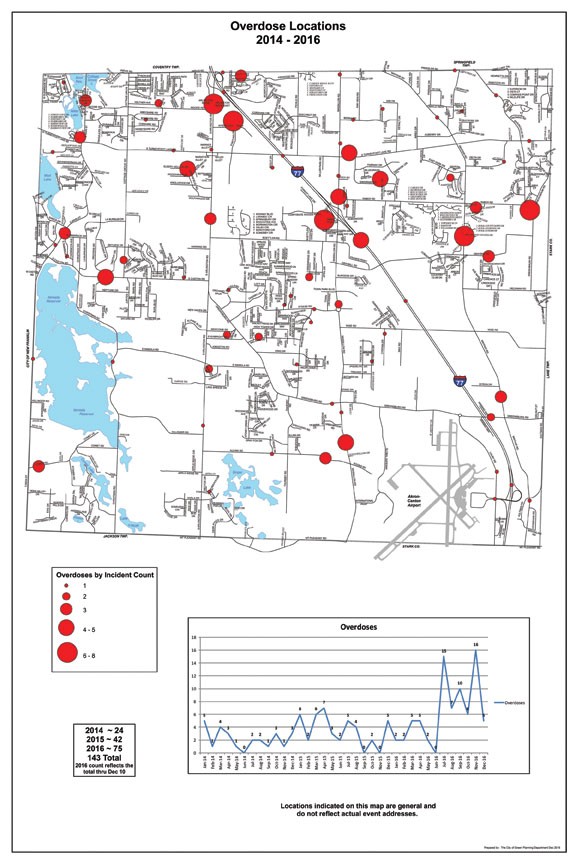

Cuyahoga County alone saw at least 663 overdose deaths in 2016. Summit County: at least 308. And then there's Hamilton County — at least 388 deaths — where Cincinnati garnered headlines last summer for the sudden appearance of carfentanil on the streets. People were dying almost hourly for a while there. Heroin supplies were increasingly being cut with fentanyl and powerful chemical analogs. "It was horrible," McNeil says. "Just horrible. Elephant tranquilizer? Are you kidding me?"

There were many articles locally and nationally about Cincinnati's summer of death and the influx of elephant tranquilizers into its opiate supply chain, but one particular one, passed along by a friend, drew McNeil's interest. "225+ heroin overdoses in 4 counties in 4 states in 1 week," it read. But because McNeil was already well into his mission by that point, and because even the most alarming numbers get glossed over in today's media environment, it was actually a small passing reference at the end of the story that caught his eye. Hamilton County Commissioner Dennis Deters was quoted, extolling the virtues of something called a Quick Response Team in nearby Colerain Township. There, among a population of nearly 60,000 people, overdoses had dropped 35 percent in one year.

McNeil was floored. He got on the phone with Colerain Public Safety Director Daniel Meloy and pelted him with earnest questions. Soon enough, the two recorded a podcast interview (Episode 25), but McNeil wasn't done with Meloy.

"He asked, 'Would you come up here?'" Meloy recalls. "And we're like, 'Heck, yeah.'" The Colerain team drove up to suburban Green, in Summit County, last winter.

In front of a crowd of nearly 100 in December, Meloy and his crew laid out the case for this new model of public service. Police officers would team up with EMS personnel and social workers to personally shepherd opiate addicts into treatment: to knock on doors and say, basically, "We're here for you."

McNeil was beaming, because this was the sort of thing that might have helped Sam. It was the sort of thing that might have tipped his family off to the full ramifications of their son's disease. He knew that it was going to help others snared in the same predicament.

"He's one of those people who cares enough not to quit," Meloy says. "He does not want anyone else to feel the pain that he felt, and he wants to be moving forward to progressive action. He's an action person, and I don't think he's going to be satisfied until it's eradicated. I think the reality is that he just wants to know that people are working. You've got to do something."

Down in Colerain, McNeil figured, they were onto something big. He brought it to Summit County, and people here are starting to see what he saw.

***

Wednesday mornings at Green's Fire Station No. 1 are a little different than other mornings. Lt. Randy Porter and members of the city's EMS squad meet with staffers from nearby Oriana House and a sheriff's deputy in a small conference room. (Green does not have its own police force, instead partnering with the county for law enforcement.) The group members — the local GO Team -- nurse coffee and run down a list of the past week's overdoses. During the week leading up to May 3, when Scene visited the fire station, six people had overdosed in the city.

Green is a small community of some 26,000 that straddles I-77 south of Akron. Its easy highway access and proximity to bigger cities makes it both a nice place to live and an easy spot to pick up some heroin, right along the freeway corridor. The city boasts a fair share of wealth alongside lower-income neighborhoods.

On Monday and Tuesday each week, Porter begins collecting the names of people who overdosed the previous week via police reports. Because the team uses public records, they're able to get around the stringency of HIPAA laws and share the information with social workers at Oriana House. This is key.

If anyone is under investigation or if there are outstanding warrants for anyone's arrest, the team leaves those names with the sheriff's office. Otherwise, on Wednesday morning, the team looks over the names — some familiar, some not — and sets out to knock on doors.

As Porter rattles off the stories behind the previous week's overdoses, social worker Stephanie Treubig begins handwriting letters to the people they'll see that morning.

At each door, Treubig (or another Oriana House colleague) begins the conversation with a variant of "You're not in trouble." Behind her, a uniformed sheriff's deputy and paramedic stand at attention. For those who've overdosed or had previous run-ins with the law, it can be an intimidating sight; Treubig sets the tone immediately.

Sometimes no one answers the door, and sometimes it's a family member or a friend. The team says they haven't run into outright resistance, but oftentimes, in the moment, the best thing they can do is simply leave Treubig's handwritten letter and an information kit about treatment options. She says that it's not surprising to have someone call Oriana House a week or two after their visit, after her words have marinated a bit.

"All of these situations are usually crisis intervention-type situations," Treubig says. "We use our clinical skills to try and talk to them and discuss treatment."

An ordinance in Green gives overdose victims some leeway with law enforcement. If a Summit County sheriff's deputy arrests an overdose victim, that person can get rid of their charge by signing up for a treatment program. They're allowed to do so three times. That sort of law encourages people to call the police and get officers to the scene in the case of an overdose. And the built-in incentive ends up getting more Green residents into treatment sooner. "Motivation's motivation," Treubig says.

And Green isn't alone in its fight: Eight communities in Summit County have signed on to the quick response movement, including Barberton, Norton, Stow, Tallmadge, Munroe Falls, Cuyahoga Falls and Akron. ("That's the biggie," McNeil says of that last city, "in terms of overdoses and where we can do the most amount of good.") That's just about 80 percent of Summit County and, based on simple laws of gravity, that's only the beginning in Northeast Ohio.

The program is new here but, using Colerain numbers as a template, the prospects are bright. A 35-percent reduction in overdoses in Summit County would mean 225 overdoses in the first two months of 2017 instead of the 347 the county actually clocked during that time period.

***

The work of Quick Response Teams is rapidly changing the very culture of police departments in Ohio. Much like the McNeil family's own education, police departments are coming to terms with the psychological foundation that addiction is a disease. These overdose victims — whether they're found slumped on a couch in their game room at home or crumpled in a Super 8 motel room at age 16, like Andrew Frye's much publicized death last year in Green — they're hurting, and the path to wellness isn't clear.

Most police officers will tell you that the prevailing cultural perspective on heroin addicts has been one of scorn. It was a misunderstood and rare phenomenon; junkies were occasional blips that wasted the time of street officers.

Cuyahoga Falls officer Ruben Miller says he caught maybe three heroin overdoses during the first five or six years of his career in law enforcement, beginning in 1995. "Now I deal with at least three heroin users a week," says Miller, who joins the Quick Response Team now and then for their weekly runs. "[Now,] it's rare to have somebody I'm transporting who isn't a heroin user. It's definitely gotten bad. ... Before, when you ran into these individuals, they were just another person you were arresting. And your perception of the problem was different."

In most Quick Response Team structures around here, like in Cuyahoga Falls (population: 49,000-plus), officers opt in to the program. Those who aren't interested in the model don't have to join; but the trend among departments who adopt this addiction-as-disease stance reveals that mindsets are changing.

To wit: "A lot of the officers are resistant to what we call social work. They want to go out and fight crime, put people in jail," Chillicothe Police Capt. Ron Meyers told the Washington Post earlier this year. "We need to make sure the officers understand this is what is going to stop the epidemic."

In Cuyahoga Falls, Miller says that even with only five months under the department's belt, results are clear: "It's a better response than we had up through the end of last year, in that we're not just giving them Narcan and sending them to the hospital — sending them into the wind, if you will," Miller says. "It's a better community response."

His chief, Jack Davis, agrees. He's seen the response trend grow from arming officers with Narcan in 2014 to joining the Perry Initiative soon after, which encouraged addicts to show up at the police station and ask for detox help. Police would link them up with their partners in treatment. ("To be honest, it was kind of hit-or-miss what we were getting on that," he says.)

As soon as McNeil and the Colerain folks presented the Quick Response Team idea, Davis quickly saw the possible benefits of the more active approach and what it could do for his community, especially while staring down 2016's mounting death toll.

"They've seen the real damage it's doing by going out on these overdose calls," Davis says of his officers. "We asked for officers to volunteer to do it; we don't ask anyone to do it who — maybe this isn't a comfortable part of policing for them. But even as a department, all my road officers have seen the devastation and impact on families. I think there is quite a bit of compassion. They realize the difference between someone who is addicted to a drug who is going to have a difficult time getting off it, versus a recreational drug abuser."

Each officer brings his or her own drive to the job, always, and the Quick Response Team has brought out even more personal angles for growth and dedication to the beat. These officers have families, many of them, and it's hard not to empathize deeply with the grieving mother and father who've just had tragedy thrust upon them in what's becoming a routine run to an OD.

"I never thought when I started this job in '95 that I would be taught how to administer a drug to save somebody," Miller says. "We learn basic first-responder first aid: direct pressure, CPR, rescue breathing. But now we respond, and everyday I take out a bag of Narcan with me so that in the event I get sent to an overdose I can — it's just unbelievable that we're there now."

He and other officers working the Quick Response Team beat have pointed out that the men and women they've met along this journey have expressed gratitude at what can only be called an opportune intervention before ultimate tragedy had a chance to strike.

***

Backdropping the microphones, one wall in McNeil's Twinsburg conference room is covered entirely with photos of Sam playing sports as a child, enjoying vacations with his family, posing in a sharp tux with his siblings at a wedding, the phases of adolescence frozen in time. "He was my guy," McNeil says softly, breaking a long pause. "He got to know people very well, and he was always one to help people and look out for them."

On New Year's Eve of 2007, Sam was looking out for a young lady as a party turned contentious. Things got bad. "He got the crap beat out of him," McNeil says. "Ended up in the ER. It was bad enough that they had to put screws in his face." Sam was given a prescription for painkillers, and you can almost finish the story from there. When the hospital refused to refill the script, he took to the streets of Akron and began buying heroin. It was cheaper anyway, and easy to find.

His family didn't know about the heroin until his sister found him passed out in the basement one day in 2010, paraphernalia strewn by his side. "At that stage, you're in panic mode. Your life changes in an instant," McNeil says.

They sent Sam to IBH Addiction Recovery Center in Akron. He did fine for a while, but he relapsed in the summer of 2011. Initially, McNeil says, it was seen almost as a failure on Sam's part. They didn't know. "When you go in for treatment," he says now, "you're taking a step and you're learning about recovery. Relapse is actually a part of recovery, and we didn't know that at all."

There's a lot that he and his family have learned since then. The U.S. saw 52,404 men and women overdose and die in 2015, including Sam. That was more than the number of gun homicide deaths that year. American families have been forced onto a steep learning curve as this crisis expands like a universe all its own. If Sam's relapses had occurred this year, in 2017, there'd be a social worker knocking on the McNeil's front door to offer a helping hand. Just a few short years ago though, that sort of thing didn't happen.

By 2015 the family had sent Sam to a treatment facility in Boca Raton, Florida, where he once again did fine for a while. He graduated from the program and, by summer, had rebuilt a wonderful life. Things were going well at work, and he had fallen in love. He and his girlfriend were expecting a child together. His father was proud.

On Oct. 23, 2015, Sam woke up and kissed his wife. She was leaving town for a church retreat, so they said their goodbyes in the early hours before the day unfolded.

Sam went to work, but something happened that morning. It's impossible to say what he was thinking when he told his boss that he was going to take the afternoon off. He said he wasn't feeling well. Around 12:30 p.m., Sam pulled out of the parking lot.

He texted his guy, and picked up a bag of heroin before heading home.

"The next day they found him in his game room," his father says. "That was it. He was gone."

***

The heroin that killed Sam McNeil was laced heavily with fentanyl, which at the time was exploding in the heroin supply chain from Florida to Ohio.

There were no clues to explain the sequence of events, the bellwether for relapse. Sam was gone, and that was it. Like many caught up in the crisis, he returned to the drug that had crept into the very core of his life. Relapse is a part of recovery, and it's become apparent to those caught up in the crisis that recovery is a process that never ends.

"From our perspective, we were blindsided by this," McNeil says. "He had gotten his life together. He was going to make it long-term. But there was so much that we just didn't know as a family. We feel like that education, had we had it, you know, maybe it could have made a difference for him. It's hard to tell."

McNeil doesn't have answers to hypotheticals, but in his heart he's got a deep and resonant empathy for those who are confronting their own eschatological struggle with addiction.

It is with those emotions that McNeil took the stage at Goodyear Auditorium in Akron, on May 20, as part of TEDx Akron. This is another part of his mission: direct outreach beyond even the podcast audience.

He spoke in April at an opiate epidemic panel at Summa Health System. Dreamland author Sam Quinones joined him onstage, proclaiming, among other things, that "drug scourges start with supply — not demand." Recall that Sam McNeil's initial painkiller prescription is not a unique plot point. This is how so many American stories begin and end.

It's how Sam's story began, but it's not how it's ending, thanks to his father. If the life hadn't flushed itself out just so — tragically, slowly — then it's hard to say whether the Quick Response Team would have ever made it up to Summit County.

McNeil has plenty of other ideas for how we can avert the typical opiate narrative. If the Quick Response Team can start as an idea in Hamilton County, where it gets tangible results for the community, and then take root in cities 230 miles away, then maybe there's a way out of this, after all. That's what McNeil believes, and that's what he'll tell you if you ask. What he finds encouraging is that people are starting to ask.

He ended his TEDx talk the same way he ended our first interview: by talking about Mt. Everest. "You need a team," he said, handing over a poker chip with the image of mountaineers emblazoned on one side. "You take that, and put it in your pocket. The next time you find somebody that you'd like to inspire, pass it to them. Let them know, 'I'm on your team. I'm on your team. I'm pulling for you.' That kind of compassion, I think that can make a big difference."