There are two prevailing opinions, depending on who you talk to, about what might happen in the race to succeed Frank Jackson as mayor.

(Yes, 2021 is still a ways down the road, but as we soak in the last years of the zombie Jackson administration, it's hard not to look ahead, if not simply for reasons of sanity. Of course, this is assuming that Jackson, who is 72 years old, doesn't unexpectedly decide to run for an unprecedented fifth term to follow his unprecedented fourth term, which now includes working three and a half days a week. Anyway ... )

The first: After nearly two decades of Frank, a period during which he faced almost no serious contender or challenger, 2021 could be a refreshing, invigorating contest featuring one or more city councilpeople, rising stars and thoughtful young voices who have more experience than running a T-shirt truck.

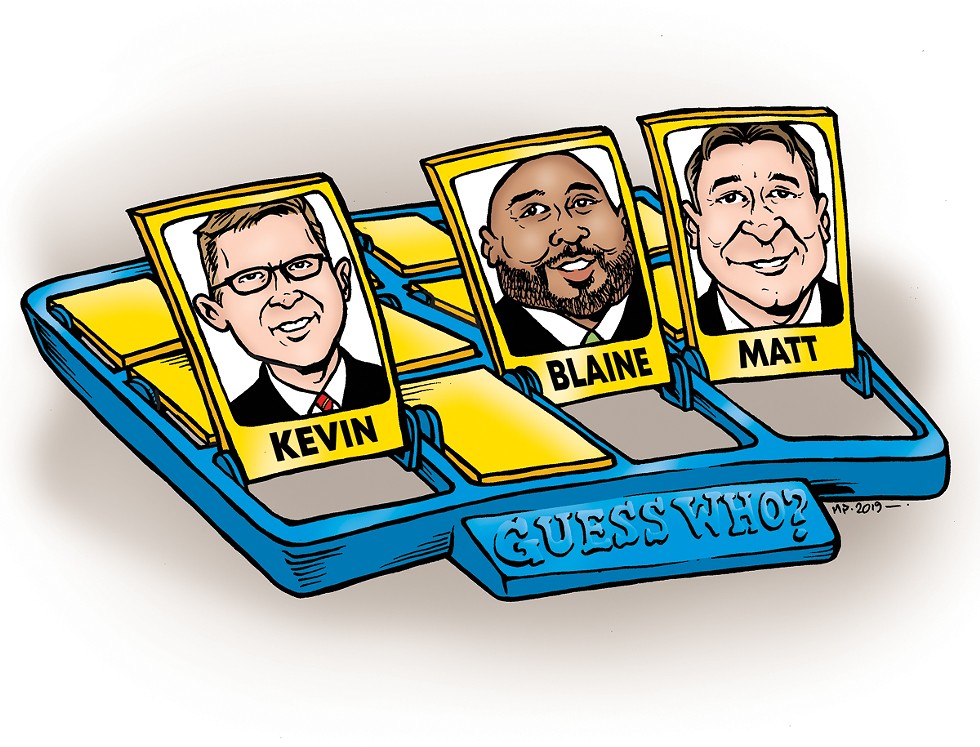

Ward 15's Matt Zone is a very likely candidate.

City council president Kevin Kelley has long been rumored to be interested, though he's demurred when asked directly. (Tangentially related: Kelley's resume — pro-business, anti-$15 minimum wage, pro-Q deal, anti-ballot initiatives — doesn't sound like one that would resonate with city voters, but it sure as hell sounds like one that would resonate with county voters if, looking at a crowded field and seeing tough sledding, he fancied a run at the county executive spot instead.)

University Circle Inc.'s Chris Ronayne is a name that always seems to pop up, though it'd be a minor shock to see him officially enter the field.

There's first-term Ward 6 councilman Blaine Griffin, a longtime Jackson acolyte who many figure will receive some measure of blessing or support from the outgoing mayor.

Another possibility from council, Ward 9's Kevin Conwell, told Cleveland.com he thought he'd be a good candidate. But as Mark Naymik wrote last week in his early look at the race, "I'll add Councilman Kevin Conwell because he likes seeing his name in print."

Whoever emerges from that pack and officially plods forward, the first opinion goes, will do so with vim and vigor, providing urgency and energy backed by policies and action for voters to consider.

And then there's the second opinion, which is most succinctly summed up by Mansfield Frazier, a columnist and community leader who unsuccessfully challenged Ward 7 incumbent TJ Dow and eventual winner Basheer Jones in the 2017 primary.

"First, if Frank Jackson wants to stay as mayor, he can," Frazier said. "And if he doesn't, he will anoint who he wants to succeed him, it will undoubtedly be a black candidate, and that will be all it takes for who gets elected next."

Well then.

Wherever you fall on the fatalism spectrum, there are some interesting facets worth examining as the landscape comes into view, two-and-a-half years before any vote will be cast. One of those is race.

It's something not many people want to talk about, obviously, but the question of how the city's demographics have played into recent elections and how they'll play in 2021 is an unavoidable one.

"People don't vote on whether police fired 137 shots into a car or not," said Yvonka Hall, the executive director at Northeast Ohio Black Health Coalition. "They vote on name recognition, and they vote for people who are like them. Frank Jackson is an older African-American. Most of the voters in Cleveland are older African-Americans. Guess who wins. But that is no different from any other ethnic group. We vote for people who are like us. That is basic politics and always has been."

In Ballots and Bullets: Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland, local attorney and author James Robenalt addresses what the black community went through to change the power structure in Cleveland, why Cleveland became the first big American city to elect an African-American mayor in Carl Stokes, and how little things have changed 50 years later. For instance, that the root causes — racism and poverty — remain largely unaddressed in the Cleveland black population's view.

"If you look at the history of how the political changes developed in Cleveland, you start with this concept: It was a reaction against what people call 'drive-by politicians,'" said Robenalt, a partner in the Cleveland law firm Thompson Hine LLP. "This is basic politics for all groups; people hate when politicians show up a month before election day, promise a lot, and then never show up again or do what they promised. These voters remember that, and do so for generations.

"[The black community] dealt with white drive-by politicians since they came to the city from down South, and they saw all the problems from that, and then realizing that them changing how that all worked was part of the reason Carl Stokes won in 1968," he said. "They saw political power was the key."

One current council member, who wished to remain anonymous, ties those changes to what's played out over the years.

"One of the things Carl and Lou Stokes brought to the table was their ability to get the older black voters out and to vote for the black candidates they were advised to vote for," they said. "The point of this is that you can't just be a business guy like Ken Lanci, who shows up at the eastside old folks' homes and thinks he'll get their votes. It won't happen because there has been a long history of that not working."

"It's not that Ken Lanci was white as the major reason he lost, but it would be avoiding the obvious to say it didn't come into play with some voters," the council member said.

A white community leader — who has fairly big business and political credentials — acknowledges that race is a factor with voters, but hard to read which way they will fall.

"Kucinich got votes from the east side when he won, but Voinovich beat Dennis when he took those black votes back from him," they said. "Mike White and Frank Jackson were both able to win initially by getting the westside white voters backing them." (It should be noted White drew those white voters in a race against George Forbes, who dominated White in black wards.)

"I still think you need both black and white backing when you get started in the Cleveland mayor's race political game," they said. "In order to win in Cleveland, you have to get just enough votes from the other side of town than where you are from."

What has changed, they said, is that the business community's ideology and purpose have shifted and evolved when it comes to local politics.

"They are not as engaged as they were in the past. It has become more of a strategy of safeguarding their established interests instead of championing new ideas that might be more beneficial but take some investment. I believe the business community has backed Frank Jackson not because of any new ideas he has, but more because they thought he was safer than people like Zack Reed or Ken Lanci or Jeff Johnson.

"The problem with them safeguarding the business establishment is it hurts the poorer eastside neighborhoods because the limited money this city has is spent downtown or Ohio City instead of Glenville," they said. "But that's not unusual in politics. People are told who to vote for, and sometimes they do so even if it isn't in their best interests."

That sentiment has been expressed over and over with regard to Frank Jackson, whose most recent campaign consisted mainly of saying absolutely nothing of substance.

"What is bothering the black community more and more is the race component to Cleveland politics," said Jeff Mixon, the president of Black Lives Matter in Cuyahoga County, who was also behind a recent short-lived effort to recall Jackson. "What has happened is that we can get black people to vote for anybody as long he or she is a black candidate, not whether they are any good or not. That's how Frank Jackson keeps getting elected. The business community has no problems with him, and the ministers back him up, and the voters on the east side are fine with that way of thinking."

And in recent memory, that has meant that despite flashpoint headlines about the police department, or the disparity in development and investment between the near-west side and the east side, or any number of topics that serve as an indictment of his tenure, Jackson coasts back to City Hall.

Take home values.

While most suburbs and parts of Cleveland have recovered to pre-subprime mortgage crisis 2008 levels, huge swaths of the city have not. Hough, Glenville, St. Clair-Superior, Union-Miles, Buckeye-Woodhill, Broadway-Slavic Village, Kinsman, Mount Pleasant and Fairfax neighborhoods are among the worst, recovering by 2017 to only 20 to 30 percent of what they were worth in 2005, according to a study last year by the Western Reserve Land Conservancy. The average eastside home sales price in 2017 was just under $24,000, 31 percent of what those homes were worth when Jackson took office in 2005 ($60,000).

"There are two large groups of African-American people on the east side, and you can win any Cleveland race with them on your side," said a longtime council member who didn't want their name used. "The first group gets some form of welfare or poverty program money, and they rent, so the home prices aren't going to play into things for them. The other group is the older population who mostly own their home outright. While they are not happy about not being able to sell at a higher price, that isn't enough for them to vote for white candidates if the pastors tell them not to."

"And remember," the council member continued, "the only way a white candidate is going to win on the east side is if they have a long history of being in the churches and with neighborhood communities, are endorsed by the business community as well, and be prepared to lose a few times in order for people to get to know their names. I don't see anyone on council now who can do that, and I don't see the business community taking a chance on pissing off the black population as long as they are getting what they ask for, which they are getting under Jackson."

But Jackson's almost done, and with no incumbent and shifting demographics in the city, it'll be interesting how those votes shake out compared to the past.

"I don't know if the changes in the racial demographics in Cleveland will change voter behavior much," said the white community leader. "But it is interesting because the political people are starting to pay attention to the racial population in Cleveland now more so than they were even a few years ago."

Here's how they've changed.

In 1990, when Mike White was elected mayor in an upset over council president George Forbes, there were about 250,000 African-Americans in Cleveland and 235,000 whites.

By 2000, there were about 45,000 more African-Americans than whites in the city. By 2010, that number was 63,000.

The last decade has seen a move in the other direction. From 2010 to 2017, there were 16,000 fewer African-Americans in the city and 8,000 more whites. With growth in areas like the near-west side and an expectation that the recent stats showing a trend of African-Americans moving from the city to eastern suburbs like Euclid will continue, the difference between black and white populations in the city could be close to 20,000 by 2020.

In elections, it could be a swing factor. In the 2017 primary, for instance, when Jackson squared off against councilman Zack Reed, former councilman Jeff Johnson and restaurateur Brandon Chrostowski, Chrostowski received just 4.5 percent of the vote in nine eastside wards with black populations of 75 percent or higher. In eight westside, mostly white wards, however, Chrostowski took home 15 percent of the vote, higher than both Reed and Johnson.

Chrostowski dismissed the idea of taking too much out of those numbers. "The Cleveland voters are educated and there is no racial bias," he said.

But as to the reason for the low total voter turnout in the election (29 percent), he was a little more circumspect.

"Poverty is a bitch that beats you down, and if tomorrow is not getting better, what faith do you have in a system that is failing you?" he said. "If you continue to wake up and every day your life is worse, why would you partake in the voting process?"

The Ballot and the Bullet author James Robenalt agreed and added that those turnout numbers, especially on the east side, will be interesting to watch as the incumbent disappears from the ballot. "The one thing that characterizes the black electorate these days is apathy, and that can be a big factor when possible change is on the horizon," he said.

And whereas Jackson could depend on the black churches and pastors to get out the vote in past years, Yvonka Hall said that the power of the churches in Cleveland may have outlived its usefulness.

"Young people are asking the questions, 'What are you doing for the people now?' and, 'What have you done for the people to change the lives in Cleveland?' They get no answers," she said. "For those young people, the churches aren't as viable as they once were, and the apathy and low turnout at elections are a result of that."

Mansfield Frazier, fatalistic as he is about what's going to happen, has a reminder of how those who are engaged in the process ought to be looking at the field.

"In the end, blacks and whites should be asking the same question," said Frazier. "Shouldn't it be about competence?"

One would hope.