"The silver lining on the Indians’ collapse," Adler wrote, "is that they now have even less reason to hang onto the racist logo. A victory may have convinced the team to hang onto the logo and the “tradition” it represents until the end of time, but they blew a 3-1 lead in the World Series—their third championship loss since 1995, and their fourth since 1948—and Chief Wahoo is an even bigger avatar of failure than he was yesterday [italics added]."

Peter Pattakos, too, the man who wrote "The Curse of Chief Wahoo," the seminal text on Wahoo opposition, in these pages [sic] in 2012, two years before the Plain Dealer took its "historic stance" against the logo, tweeted that the World Series loss certified the curse's legitimacy and ongoing influence.

Change the name, change the logo, exorcise the most legit curse in sports and win clean. It's an infinitely better story, anyway.

— Peter Pattakos (@ClevelandFrowns) November 3, 2016

In the meantime, the Curse of Chief Wahoo is officially the most successful curse in sports

— Peter Pattakos (@ClevelandFrowns) November 3, 2016

Vox.com followed suit. Leaping on the news cycle's bandwagon, Victoria Massie argued that the curse of Chief Wahoo itself "demands that Cleveland recognize Native Americans as more than mascots."

Well, all of this is fairly yucky and stupid, if you want my take, though by-and-large well-intentioned: Its cumulative effect is to suggest that Cleveland and its fans are so morally bankrupt, so Faustian, that the only way they would surrender to the demands of basic cultural sensitivity would be in order to vanquish a curse, to thereby win a championship, to countervail against decades of almost-titles that would have been ours but for the curse. Folks who advance this view are having to strain ever more gymnastically to do so with a straight face.

Those who are still using the Curse of Chief Wahoo as a blanket city-wide scourge, for starters, must reckon with the Cavs championship in June. Was that an anomaly or what? Vox, for its part, actually cited the fact that the Cavs "had to rally from a 3-1 lead by the Golden State Warriors" to win its first title as evidence of the curse. Consider your pardon begged. The Browns, too, must be countenanced, but in a different way entirely; that is, in the sense that their failure and dysfunction are so absolute that to suggest they're affected by supernatural forces of any kind gives them way too much credit.

The earnest curse-defender must then look at the preponderance of evidence and decide that its sphere of influence is limited to the Indians. Here, though, he finds himself on stabler terrain. And the 2016 Game 7 loss is presented as a kind of primary document.

But this is silly too, I'm here to submit.

The Cleveland Indians, with a rotation of "one trustworthy starting pitcher, a fringy innings eater, the Biblical Curse of Blood, and a child," quoting here the second-best lede of the postseason, courtesy of the Ringer — this is the best, a three-graf gem from the New York Times' Waldstein, Hoffman and Mather — took Cleveland fans on the longest and most exuberant roller-coaster ride they could have, in an October that everyone and their brother at Yahoo counted them out of. Despite not taking home the ultimate prize, the old Indians' magic was back at the corner of Carnegie and Ontario. The summer and balmy autumn of 2016 were incredible seasons to be a fan.

So what of the curse? Is its sole function to prevent the Cleveland baseball team from winning one game, one less than the maximum number possible? And out of curiosity, if the Indians hadn't made the playoffs at all, would the curse have been considered more effective or less? Proponents might say — and have said — less, that the curse works best when tragedy is amplified by proximity to the ultimate goal. The fashion of defeat is key.

"[Russell Means'] curse specifically directs that the team make it to the seventh game of the World Series, with a 3-run lead, and lose on a walk-off grand slam home run on the very last pitch thrown. He wants the loss to be THAT excruciating for the city and its fans," writes curse proponent Ed Rice in a piece originally penned for the Bangor Daily News.

But for heaven's sake, what about the dramatic and decisive fashion in which the Indians dispatched both the Red Sox and Blue Jays, even, in Toronto, as a Wahoo legal battle was waged in a Canadian court hours before Game 3? What of Rajai Davis' home run? That was the opposite of excruciating for most fans, in fact nearly as triumphant as the Cavs' assorted fourth-quarter heroics of their own Game 7.

It's just a very delicate argument to make, and for that matter, so is arguing that Chief Wahoo is a "bigger avatar of failure" today than it was yesterday. That might be technically true, but only because yesterday — two days ago now — Chief Wahoo was the de facto avatar of wild success, overcoming unlikely odds, Rust Belt grit, Francona, Lindor, Kipnis, Miller, Kluber and the "unbridled enthusiasm" it was originally designed to induce. The Indians might have one more World Series loss to their name, but they also, crucially, have one more World Series appearance, a distinction that 28 other teams, in 2016, could not claim.

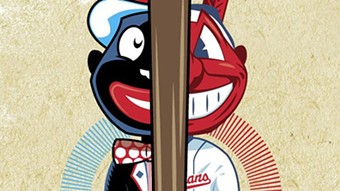

Let's not get carried away. Chief Wahoo has got to go. No question. It won't be abandoned by fans anytime soon, and certainly not with the influx of Wahoo-branded postseason merch flooding the market, but the Indians ownership has got to get rid of it. I won't rehash the reasons why. You've read them before. My point here is that getting rid of Chief Wahoo should have nothing to do with dispelling a curse and everything to do with conscientious leadership.

Unfortunately, on this definitive issue, conscientious leadership is no longer on the table. I've written that the future date when the Indians abandon Wahoo will be precisely the day on which it becomes financially attractive to do so. If the Dolans do decide to re-brand or axe Wahoo now — and there will be no "quietly abandoning" Chief Wahoo, by the way, as Adler instructs, not in this day and age — it will only be because they have succumbed to mounting pressure: from a growing number of uncomfortable fans and employees, if not from the MLB Commissioner himself.

Given all that, from the perspective of fan base psychology, a World Series victory would have provided a much stronger case to sever ties with Chief Wahoo than a loss.

I guess this is the dissenting opinion, but to me the line of argument is clear:

1) Chief Wahoo is deeply enmeshed in the Cleveland sports fan's whole identity template. It's difficult to disentangle Chief Wahoo from the fan identity at large. If you do, it's a conscious choice. Disentangling takes effort and is often really sad. (A lot of bloggers at national outlets haven't quite nailed this yet: Though the logo may be racist, fans' affection for it (usually) is not, and to dismiss every Wahoo diehard as a racist goon gravely misunderstands the issue, IMHO). And though for some, standing up against offensive imagery seems like an easy, obvious stand to take, it still requires you to take a stand. And as a fan, that's a bummer because you want to #RallyTogether, you want to be #Allin, and even minor concessions to the #DeChief crowd can make you feel, in some ways, like a traitor.

2) Until very recently, the most central and deeply ingrained component of the Cleveland sports fan's identity — of the collective psyche — was the fact that it was tortured; the fact that fans were quote unquote "long suffering."

3) We are no longer suffering.

3.b) e.g. "The drive. The fumble. The shot." is now "The Block. The Shot. The Circumstance."

4) The soul or id of the fan base is transforming, thanks to the Cavs' and the Indians' performance.

5) Efforts to re-brand perennially awful teams anywhere without corresponding efforts to improve those teams are always perceived by astute fan bases as "lipstick on a pig." No one cares about new uniforms or new logos or new scoreboards if the team itself is garbage. But if owners make sound decisions and invest in quality players and thus energize the fan base, everybody wins. (Have a look at the Cavs' Championship parade).

6) Transforming — or maybe even, like, transfiguring — a fan base's soul is the hard part, much harder than cosmetic stuff at any rate. Now that fans are coming to grips with what was once a bewildering idea — having winning, Championship-caliber teams — there's no reason they shouldn't accept or embrace a new face to go with this new identity.

7) A face is a really important part of one's identity, especially when it wants to be out in public a lot.

8) The Cleveland Indians are a very good baseball team. They are innovatively managed by a man presumed to be destined for Cooperstown. The team's core players have been signed to long-term contracts. The starting pitching staff, when healthy, is perhaps the best in the majors. There is little doubt that, barring catastrophe or bad luck, this team won't continue to compete at a high level for several years, i.e, make the postseason, i.e. be out in public.

9) A World Series victory, more than any of the above factors in #8, is the clearest indication that a team is good. It'd be a signal, in this case, especially so close on the heels of the Cavs' title, that Cleveland's — that is: the teams', the fan base's, the city's — soul is a champion's soul at last.

10) New soul. New face. (New face = something other than Chief Wahoo.)

I've got some other thoughts on the ownership, in particular how claiming that they are paralyzed on the Wahoo front because of their deference to the fan base is a defense that's positively festooned in horseshit. But I'll spare you that for now.