Carrie Wood, a former staff attorney for the Ohio Innocence Project, who helped shepherd this case to fruition, says that whatever investigation did take place in 1995 was marked with "tunnel vision," a common trait in cases of wrongful conviction. "You jump to a conclusion about Eugene, Laurese and Derrick, and you ignore the evidence that doesn't fit with your theory of the case," she says. "When you ignore evidence of who the true perpetrator was and you ignore evidence of what happened to that victim, you do a disservice to the victim as well as to the people you wrongfully convicted."

There were holes in the case, of course; the guys never stopped proclaiming their innocence, and evidence existed somewhere to back them up. The truth was missing from the official story.

Johnson remembers the Innocence Project attorneys telling him, look, if you've got a murder with three convictions on the table, there's going to be more than seven pages in that report. As litigation continued over the legitimacy of the state's gunshot residue testing protocol — a process later deemed unreliable — the defense of the East Cleveland 3 turned toward the void, that gulf between the prosecution's story and what really went down on Strathmore Avenue on Feb. 10, 1995.

"We all knew, once that came in, that's when I knew it was over with," Johnson says. "It could have been resolved 20 years ago."

***

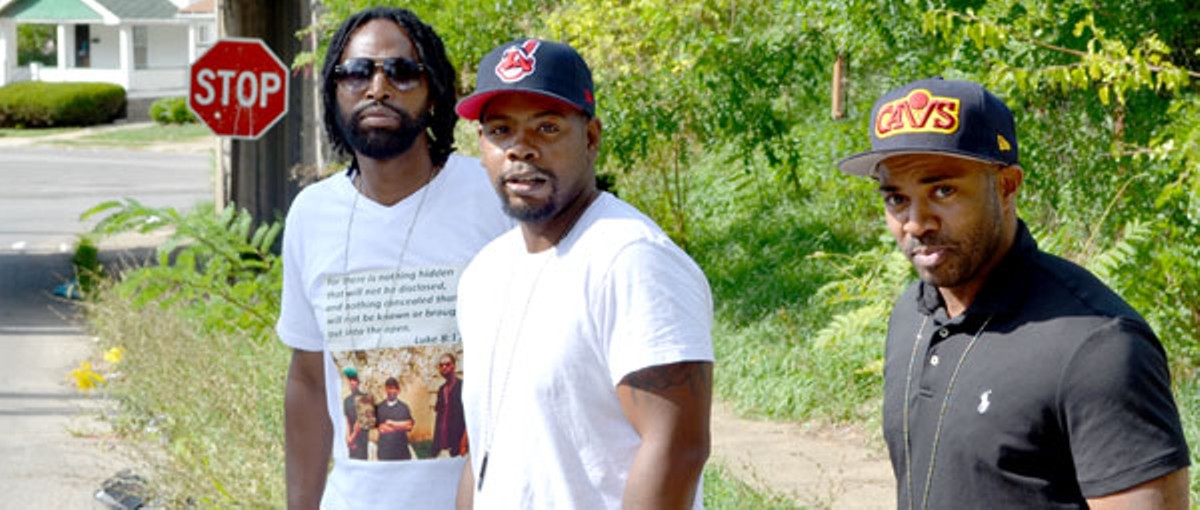

Almost in unison, the three men thump thick stacks of paper onto a table at the East Cleveland Public Library. Only a sliver of the thousands of pages of trial transcripts and appeals records, the documents they've brought today include a trove of witness statements and facts from early 1995. They've only been out of prison for a year at this point, and the papers they have in their possession today could have stopped this nightmare before it began. It's an alarming notion.

"The first few pages was the only thing I had ever seen before – like the first five or six pages on top," Glover says, describing the portion of the police report that the guys had access to for most of their time in prison.

After continuous public records requests via the Ohio Innocence Project — including particular pressure applied by appearing in-person at the East Cleveland Police Department — the full police report was delivered to the attorneys and their clients. Just like that, after all those years, the paperwork was discovered.

Contained within the nearly 70-page report were additional witnesses with alternate suspect theories and information that could support a specific motive for the murder of Clifton Hudson.

"It didn't have to go this far," Johnson says. "They took our story and deliberately put us in that situation, planted evidence to make it seem like we done the crime. They hid the truth for 20 years that brought all the pieces together. It didn't have to go this far. It could have been resolved 20 years ago. We got apprehended, arrested, questioned, and, even when we was going on trial, I believe that they knew." Of course, he and his friends and family were certain of that during the first trial. But now, equipped with raw evidence, his deep voice sometimes gives way to astonishment.

On Feb. 12, 1995, two days after the murder, Monica Salters, a resident of Strathmore Avenue, called the East Cleveland Police Department. She said her sons, Dante and Gary Petty, saw the shooting go down. Dante was 10. Gary was 8.

She told detectives — and the children later explained themselves — that Dante was walking north on Strathmore, coming toward the scene of the crime from the opposite direction that Tamika Harris had been walking. Dante was behind the black Blazer. He saw a man walk out of the post office parking lot, approach Clifton Hudson and shoot him.

At the same time, Wheatt's father was working the neighborhood in an attempt to bring more witnesses into the open. He was showing up at the department almost daily, insisting to the chief that there was more to the story. In the police report, he appears frequently in most conversations with other witnesses and neighbors, piecing together an investigation of his own. Wheatt's father insisted that the real shooter had fled up the hill and onto the railroad tracks nearby. Several witnesses who spoke with police mentioned seeing a man run in that direction; the visual is repeated in multiple interviews with detectives.

In the weeks and months that unfolded, Wheatt's father had rounded up additional witnesses who backed up the Petty boy's claims about the shooter's approach. He had identified an alternate suspect, whom detectives didn't interview until May. (The other suspect, a post office employee and neighbor, denied any involvement in the murder.)

Wheatt's father died in 2008.

***

Through everything, though, police relied on the young girl they met first at the crime scene: Tamika Harris.

In 2004, she recanted her testimony and insisted she believed in Johnson's innocence.

"I was 14 years old. I told the police what they wanted to hear," she said in a hearing that temporarily freed Johnson and granted him a new trial. It was a revelatory moment. "I am older now and realize that I was mistaken."

Glover and Wheatt remained in prison during this time from 2004 to 2005. ("I used to think all along that Tamika was never there," Glover says.) Wheatt remembers watching Johnson's court appearance on the news, eyes gripping the screen in disbelief and hope.

In one of the more shocking twists to the entire case, the Eighth District Court of Appeals overturned Russo's ruling and returned Johnson to prison in June 2005. This was before the Innocence Project had joined forces with the men. He had been out for nine months — slowly readjusting to life in the real world, much like he and his friends have been doing now this past year — before his name landed on an arrest warrant. The recantation wasn't enough, the court ruled; there was still the matter of the gunshot residue found on a glove in his jacket pocket.

"That messed me up," Johnson says. "I ended up in a mental hospital in 2005. To get a taste of freedom and get it snatched away ... I think it took me like four years to just come mentally — come to grips back to myself."

Once again, the journey restarted for him. He reunited via the postal service with Wheatt and Glover in separate penitentiaries. The journey brought the Ohio Innocence Project to their cause in 2006 and, later, the journey forced those long-lost documents into the light.

Trudging along at a glacial pace, with nary a moment for disillusion, the East Cleveland 3 found themselves in Russo's courtroom again in 2015, when she overturned the original convictions of all three men, this time with the compelling information from the police reports on the record. From there, it took another court struggle to garner a new trial one year later — a necessary step in completely clearing their names. (The men remained out of prison during that last year, essentially on house arrest.)

As recently as January 2016, County Prosecutor Timothy McGinty's office was pushing back against the idea of a new trial, opposing the idea and asserting that gunshot residue was still a slam dunk. Never mind Harris' recantation, the state argued, there was physical evidence to confront.

As Innocence Project attorney Brian Howe pointed out during a January 2016 hearing for a new trial, "The state can't put a time stamp on the gunshot residue. Doesn't know if it was four months old or if it came from contamination at the police department."

Aug. 15, 2016, was the first day of the new trial for the three men. They'd waited eons for this opportunity, and the moment whizzed by almost as soon as it arrived. Under McGinty, the state dismissed the murder charges against Johnson, Wheatt and Glover. It was all over.

The new trial flew by in a flurry of emotions. The men entered quiet and reserved and soon flashed brilliant smiles before the press scrum, arms wrapped around friends and family. They were each wearing gold necklaces emblazoned with their likenesses and the name that will never leave: East Cleveland 3. (Johnson's was tucked beneath a checkered olive-green suit.) Their lives resumed, all at once.

"This isn't about one side or another winning, this is about the Constitution winning, this is about justice winning," Russo said. "You are free to go."

(To date, the East Cleveland Police Department has not identified another suspect in the murder of Clifton Hudon. No one else has been charged. The police department did not respond to requests for comment.)

The profundity of the moment recalls Ricky Jackson and Wiley Bridgeman's release from prison two years ago in Cuyahoga County. Jackson lays claim to the longest case of wrongful incarceration in U.S. history. He was in prison for 39 years for a 1975 murder.

"He's one of my heroes," Johnson says. "He's real humble."

Johnson and his friends have spoken here and there to the press and to law students at Case Western Reserve University. They say that that's sort of a standard question: whether or not they're bitter about what happened. The East Cleveland 3 say that you can't be. They're looking forward to what's next.

***

Only recently has the struggle that follows exoneration been a topic of mainstream reporting and conversation. The East Cleveland 3 claim the 1,864th, 1,865th, and 1,866th names in the National Registry of Exonerations, a long list of men and women who've endured a brutal and unnecessary spin through the cogs of a criminal justice system.

"Now that the case is over with, that still hasn't sunk in that we're free," Glover says. "But at the same time it still feels like parole because the whole job search and all of that; it feels like we're on parole. I was always hearing before we got out that it was hard for people to get jobs — especially like for people who went to school, it's still hard for them to get a job. But this is just — I just always thought when this day came, once we get free and get our name cleared, I just knew it would be more opportunity for me than what it is. It ain't like that. It's a struggle. It's a struggle.

"I'd rather struggle out here than go through that again."

They're working to land jobs, massaging helpful connections via their attorneys. But no dice so far. Someone in the mayor's office suggested Glover attend one of those community meetings for people seeking help with their resume. "A resume for what?" he asks rhetorically.

In late September, Johnson, Wheatt and Glover met with a job services rep at the East Cleveland Public Library to discuss possible employment opportunities in the area. The meeting was arranged by Russo, in fact. Glover said they'll hear back soon on the next steps in that process.

They set up a GoFundMe page — though it floundered — and they and their families have toyed with various avenues for outreach, hoping to get their story in the spotlight. There are lessons to be learned. They've even considered setting up a Facebook page. ("That social media is so big now," Glover says. "Like, everybody — most likely when you see them looking at their phone, that's what they're looking at.")

Furthermore, it's unclear what governmental compensation may be coming their way. Ricky Jackson, for instance, received $1 million in 2015 for his 39 years behind bars. The state has not conceded that the East Cleveland 3 were wrongfully convicted and incarcerated. Charges have been dropped, yes, but the state has yet to pave the way for recognition and compensation by declaring them exonerated.

"It's painful for them for the state to continue in that tunnel vision and not to say, listen we screwed up," says Carrie Wood, who has since moved on to the state's public defender office from the Ohio Innocence Project. "We stole your life from you and we apologize for that. It's amazing the denial of that to someone and what it does to them and the impact that it has. And then all of the things that flow — the job and the financial compensation and all the things that help a person start to heal. The denial of that, which stems from the state's inability to say that it made a mistake, is truly huge."

In other news, there's plenty to celebrate. Wheatt got married. Johnson is crafting a book, culled from hundreds of pages he wrote during his time in prison. His goal to is tell his story, his friends' story, and to explain to the public how things like this happen to people.

This case, a disarmingly thorough house of cards, was not a mistake; regardless, it certainly never should have happened. But here they are.

"To get wrongfully convicted together, to go through the nightmare together, and to get released together," Johnson says. "That's the beautiful thing in this whole picture: that strength, that's what the East Cleveland 3 represents. That faith."