Back up about 50 years and you have the prequel for Mrs. Clinton -- in terms of passions generated for and against -- in Maria Eva Duarte de Perón, a movie actress and radio personality who married Juan Perón and became the first lady of Argentina from 1946 to 1952. Eva was a lightning rod for passions of all kinds, and the musical Evita traces her brief but phosphorescent trajectory from obscurity to celebrity demi-goddess to her untimely death at age 33. This production, handsomely mounted on the Palace Theatre stage, still sizzles and pops with the inventive staging created originally by director Harold Prince and choreographer Larry Fuller. But less than effective casting in two key roles and some spongy dance routines deflate a lot of the show's power.

Of course, one song from the score by Andrew Lloyd Webber (music) and Tim Rice (lyrics) is well known by anyone who's been semiconscious for the past 25 years. But there's much more to Evita than the weepy stanzas of "Don't Cry for Me, Argentina." The play shows how Eva rises from her dirt-poor origins, beds a series of men, and uses them as stepping-stones on the way to her destiny as a national icon. One sequence, literally using a revolving door on Eva's bedroom to spew out one hapless lover after another to the tune "Goodnight and Thank You," is a quick and devastatingly clever way to demonstrate this determined woman's mind-set.

Eva gains a modicum of fame on her own as an entertainment celebrity, but once she meets army colonel Juan Perón, she sees her chance to mold him into a leader and herself into a figure of public adoration. Along the way, the dislike she generates among members of the upper crust only fuels her determination, and when Perón is finally elected to the presidency, she uses her position as first lady to advocate for the poor, establishing hospitals and orphanages. But her cult of personality grew larger than any populist works, and evidence of fascist leanings and the increasingly dictatorial grip of the Perón government tainted her final years.

Using a fictional Che Guevara as a narrator and commentator, the story is spun in operatic style on a set dominated by scaffolding and screens showing stills and newsreel footage of the Peróns at various stages of their lives. These black-and-white images are almost more riveting than the live action onstage. This is particularly true in regard to Eva, as played by Sarah Litzsinger. Her last name may not mean "light singer," but if it did, it would be apt, since her voice tends to disappear in the lower registers. Pretty and slight, Litzsinger doesn't possess the physical presence or the charisma to craft a believable Eva, grimacing and swaggering like one of the Little Rascals as she attempts to convey her character's ferocious but subtle gamesmanship.

Litzsinger pales even more in comparison to Keith Byron Kirk, who invests Che with an electrifying command of the stage. Swinging from grudging admiration of Evita ("You have to admit, she had style") to revulsion at her take-no-prisoners ethics, Kirk nails his songs and uses his wry facial expressions to bring needed humor to the proceedings. While Philip Hernandez' Perón is serviceable, he tends to mug more than necessary and never explores the depths of this flawed man.

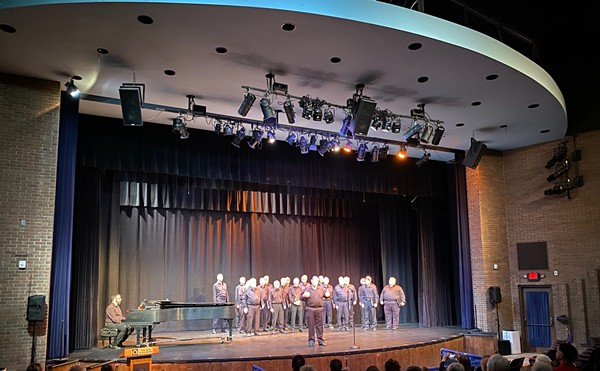

The large company of performers supporting the leads sings with unquestioned authority, but several of the dance routines are executed carelessly. Several times, the aristocrats of Buenos Aires appear in a clotted group and are supposed to move in miniature lockstep as a single entity. But due to less-than-rigorous touring company supervision or just lack of interest, the group is only loosely connected, and the humor -- not to mention the metaphorical impact of this closed society moving and acting as one - is forfeited. Even the musical-chairs sequence, in which Perón ascends to power as he and the colonels sing "The Art of the Possible" while circling an ever-decreasing row of rocking chairs, lacks the precision that makes a good scene great.

Upon her death, Eva Perón was a beloved and idolized figure in Argentina, while detested in other places for her self-aggrandizing immorality. From any perspective, she was a larger-than-life figure who, in this production, is regrettably rendered in miniature.