German expatriate Kurt Weill, for a brief time Broadway's most accomplished tunesmith, took his crack at the novel. Unfortunately, he succumbed to a heart attack after writing four exquisite numbers. His lyricist, Maxwell Anderson, tried to no avail to interest Irving Berlin in completing the project.

Gene Kelly tried for years to turn it into an MGM musical for himself and Van Johnson. It was ultimately brought to the screen by Reader's Digest in a prepubescent kiddie hoedown with a treacly score by Mary Poppins's Sherman brothers. In 1985, producers Rocco and Heidi Landsman came up with the inspired notion to couple Twain's masterpiece with the distinctive American sound of country songwriter Roger "King of the Road" Miller. The result was the Tony-winning Big River.

It shouldn't have worked. Up to the time he wrote this show, Miller claims to have seen only one musical. Oliver! aside, great novels tend to turn to stone on the musical stage. Yet here, a magical alchemy occurred. Miller used sassy fiddles, wry banjos, a church organ, and plangent harmonica chords to etch gospel spirituals, bluegrass-flavored odes to boyish camaraderie, melancholy slave anthems in the "Old Man River" mode, and invigorating vaudeville dance routines. He not only created a musical approximation of Twain's rascally prose; his gifted score went even further, evoking the nostalgic poetry and mythologizing of history that we find in John Ford's cinematic reveries on America's past.

Like a superbly illustrated edition of a classic, this rambunctious musical bursts with indelible visualizations of the book's wonders. These include a young girl singing of her loneliness at her dead father's coffin; Huck and runaway slave Jim on a raft, trying to see the world through each other's eyes; and a fraternity of runaway boys playing pirate games and singing of the unfettered joys of boyhood ("We can hoot, shout, and holler!").

William Hauptman's libretto is a masterful piece of carpentry. Although eschewing the novel's deadly Grangerford/Shepherdson feud and planing down some of the rough edges, Hauptman manages to preserve the story's shaggy picaresque structure and the novel's voice by leaving Huck as the narrator, with Twain himself silently walking through the show as an approving specter.

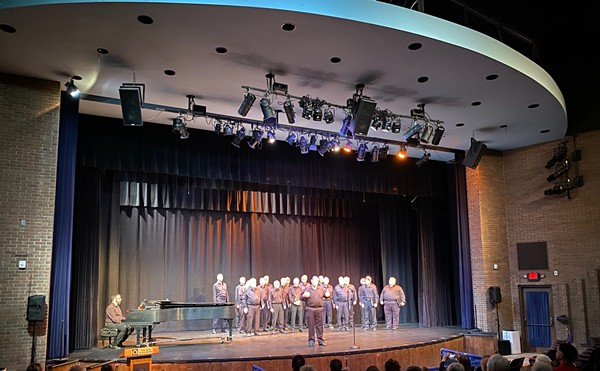

In Porthouse Theatre's production, the work is infused with the triple-X moonshine it requires for the proper kick. Its youthful exuberance never winds down. Director Terri Kent's work has never been so effortless and joyous (if only she would learn to direct to all sides of the house). She's acquired a wonderfully adept cast that, in broad, bold strokes, gives life to Twain's multitude of eccentrics.

The show is written to be played by young adults, moving Huck and cohorts from early teens to burly postpubescence. Even though in his early 20s, Andrew Tarr is easily able to play adolescent sexuality. As literature's most famous scamp, he is the male counterpart of Lolita. His interpretation of Huck is a golden satyr boy/man, dangerously perched between adolescent wantonness and the sensitivity that comes with young adulthood. He has the aw-shucks humor of a burgeoning Will Rogers. Kissed by the pretty young Mary Jane, Huck experiences his first awareness of sex. His face lights with wonder and desire as he proclaims, "She laid her silky hand on me, and I just about died." Though he is supported by an able cast, Tarr's effulgent performance has enough wallop to transport the evening to Nirvana on its own.

There's a charmed symbiosis here between a dedicated company and a soulful show. The majestic Brian Johnson camouflages his opera origins with a Jim of beguiling grace and innocence. Eric van Baars, as the oily, hyperkinetic Duke, and David Vosburgh, as the anything-for-a-buck King, bring an enjoyably satanic roguery to the proceedings. Dudley Swetland's monstrous drunken Pap Finn, enacting a blues diatribe about the "goddam guv'ment," offers a dash of musical heat. Eric Lualdi gives us an overgrown rapscallion of a Tom Sawyer, appropriately in need of a spanking.

Raynette Smith's set, with its river of silvery light, brings to life the main metaphor of the novel. The set's depiction of a rough-hewn pre-Civil War South is made even more effective by Kazuko Inoue's lively costumes.

A perfect summer pleasure, this is a rare melodious merger of literature and song. It's guaranteed to make readers hum and hummers read.